Trauma is usually the result of an exceptionally stressful personal experience in which the individual‘s possibilities and resources are insufficient for coping with it. This leaves long lasting traces. In the personality. In the soul. In the body. And in the energy system. The latter can provide us with valuable clues how we can touch traumatized people with Shiatsu in the best possible way. Because the traces show a certain pattern: the matrix of a trauma. This is the 1st part of an extermly interesting article from Mike Mandl, which we encourage you to read.

The term trauma comes from the Greek τραῦμα and means wound or injury. In my nearly 30 years of Shiatsu practice, I have been able to touch a great many of these in a variety of settings. I have given Shiatsu in a hospital for child psychosomatics. The background stories of the little patients can almost break your heart. Violence. Abuse. Neglect. Even more dramatic stories came to me within a project of the International Academy for Hara Shiatsu. With treated refugees, to help them with integration. Their background: War. Murder. Mass rape. Torture. Loosing the whole family. Far less emotionally challenging, but no less exciting, was my work in the rehabilitation department of a large clinic, where the focus was on physical traumas that proved resistant to therapy, simply because the psychological component was not sufficiently considered in the conventional approach.

All of these activities have led to an intense exploration of the concept of trauma, and thus to a focus in my practice, where I have been able to explore a wider variety of this so existential topic, from treating incest selfcare groups to accompanying terminally ill individuals to working with the more commonly spread traumas, that can happen in one’s life.

And it is not only my essence: Per se, it can only be fuzzily predicted which events lead to a trauma for which people, because many factors are co-deciding whether it comes to the long term manifestation of a profound injury in the personality structure or not.

It depends on the individual process of becoming, on the character, on the psychological and emotional immunity, on the stability of the life circumstances, on the available resources, on the resilience, on the regulatory power of the nervous system, on the age, on the stage of life, even on the ability to give one’s life a deeper form of meaning or the connection to belief or spirituality. In addition, there are many other influencing factors.

Not everything is a trauma

It is an outdated approach, that trauma must always be one overwhelmingly tragic event. Of course, serious accidents, exposure to violence or natural disasters have a high traumatizing potential. One singular event (Type I Trauma) can be so shocking, can be so stressful in its intensity, that there is no possibility for the person to deal with the corresponding situation directly – and also afterwards. But also much less severe life experiences can lead to traumas, which hardly differ in their felt impact and their symptomatology. If a sum of negative experiences with a high emotional charge extends over a longer period of time, this can leave just as far-reaching traces in the body and mind (Type II Trauma) as one singular shocking event. Many of these Type II Traumas develop in childhood, because children have far fewer ways of dealing with difficult situations than adults. In my practice I could observe a steady increase of clients with Type II Traumas, especially after the beginning of the CoVid crisis, certainly because the setting of the CoVid crisis contained all the ingredients to bring dormant traumas to the surface.

Nevertheless, I would like to draw a clear dividing line at this point. Because the term trauma is often used in an inflationary and careless way in the general vocabulary and in the media.

It seems to be fashionable to have a trauma and one speaks far too quickly of a divorce trauma or a workplace trauma, when people experience challenging life circumstances. However, stressful situations need not necessarily lead to trauma if one remains capable of acting despite the stress and can even grow from it in the longer term. This generalized usage is unfair to all those who have experienced truly severe traumatic experiences and suffer from extensive trauma symptoms. This also applies to the terms depression or burnout. There is a big difference between a low mood and a real depression, just as there is a big difference between fatigue and a real burnout.

The Yin and Yang of the nervous system

Independent of the personal situation and history of any trauatizing process, it affects our nervous system in a very specific way. The autonomic nervous system has – from the TCM point of view – a yin and a yang aspect. The yang aspect is represented by the sympathetic nervous system. It puts us in a state of heightened activity. It controls our arousal potential.

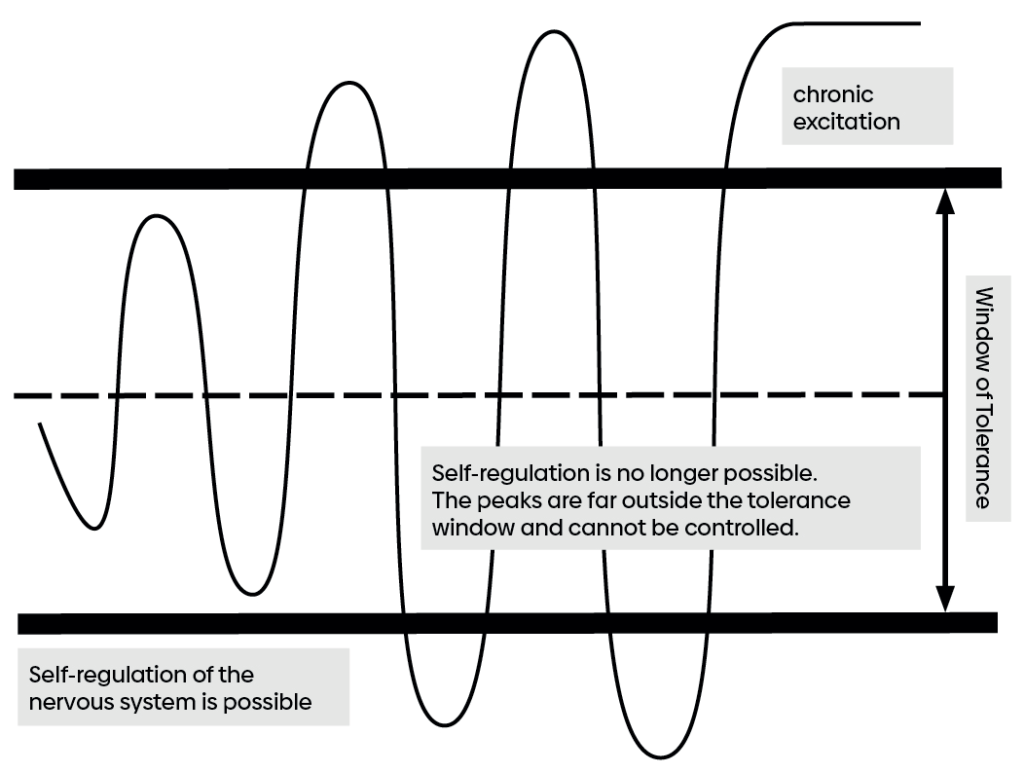

The parasympathetic nervous system represents the yin aspect. It is responsible for any form of calming. As is the case with yin and yang, a dynamic and rhythmic change between these two aspects is an expression of a healthy balance and this change should take place within a certain range of tolerance. To understand this process, we can work with an image: There is a ceiling. And a floor. If activation and relaxation phases move within these limits, all is well. How far these limits are set is again an individual matter, but it determines how stress-resistant and resilient we are. If the distance between the ceiling and the floor is small, the amplitude can quickly shoot through the ceiling or drive through the floor. With a large distance, on the other hand, there is sufficient buffer to be able to absorb even large stress intensities. This window of tolerance is primarily shaped in the first years of life, above all by the relationship to close caregivers.

The characteristic of a traumatizing event is that the sympathetic nervous system shoots through the roof. A threat of any kind activates the fight, flight or freeze mechanism beyond its tolerance range, making conscious control no longer possible. The result is a feeling of helplessness and powerlessness. An overwhelming feeling that leaves no room for maneuver. The sympathetic nervous system pumps energy into the body, but it cannot be converted. It is as if one were chasing high voltage through a conduction system that is not made for it. The conduction system is completely overloaded. The fuses blow. The drama of trauma: Even when the triggering situation is over, the relieving stop signal of the body remains absent. The condition begins to manifest itself, starting from the nervous system and moving into the body and into the mind and soul. And there it can settle in and bring far-reaching consequences for the entire way of life. Over years. Over decades. The affected persons are usually integrated into everyday life in a normal way. But for them it is not a normal everyday life. It is a major challenge. Like driving with the handbrake on. It is possible. But with much more effort and with a lot of friction.

This is, of course, a very simplified representation of a trauma process, but the crucial mechanisms behave in this way and help us to understand the subject of trauma from the point of view of Shiatsu.

The energetic structure of trauma

Related to primary survival mechanisms, the nervous system acts in a characteristic way, regardless of the different trigger factors. And our energy system also shows specific patterns, as the body and our energy system cannot be separated. It is a chain reaction that begins with the kidneys. In the view of TCM, any form of uncertainty, fear or shock affects our kidneys. This in turn activates the partner organ, the bladder, which controls the sympathetic nervous system with its meridian course. The bladder activates the fight and flight mode – a completely normal process. Within the tolerance limit, the system can regulate

itself again. But trauma is a different story.

The bladder energy shoots through the roof. The kidney energy rattles into the basement. A massive overactivation with simultaneous deeply felt fear. This is the initial situation.

The bladder has too much energy. The kidney has too little energy. As a consequence of the continuous tension of the bladder meridian, the excitation threshold of the central nervous system is significantly lower than before the traumatizing event. This is often accompanied by hypersensitivity, that can reactivate the state of anxiety stored in the kidneys even in response to small stimuli. This is referred to as hyperarousal. Even supposedly insignificant triggers such as a particular sound, a specific light effect, a smell, a message, or a photograph can trigger a disproportionate state of arousal. This state costs an enormous amount of energy, which is sucked out of the kidneys – our storehouse of the essence Jing.

(to be continued)

- Touching trauma, understanding trauma – part.2 - 29 August 2023

- Touching trauma, understanding trauma – part.1 - 24 August 2023

- Common errors in Shiatsu - 23 January 2023