Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return

“Our bodies are made from the burnt embers of stars, which scattered across the Galaxy in giant explosions, long before gravity pulled them together to form the Earth.” [1]

So begins the book Living with the Stars [2] opens, in which an astrophysicist and a doctor outline the links between our small physical universe and the great cosmic universe. What’s fascinating about this sentence is that we immediately see the link between organic creatures and the stars, as well as the presence of a third organizing force: gravity. A force that exists in the infinite void of space, organizing both matter and movement. I refer the reader to the first article on the void (空 Kōng), where he will find an insight into an organizing force as described in ancient traditions.

This is where the heart of our journey through traditional language lies. How do Chinese and Buddhist traditions describe the organization of form through space? What links do our Far Eastern traditions have between matter and space, body and consciousness?

Or, as the Yellow Emperor asks:

“How can the small, the great, the superficial and the deep unite their diversity into one single thing?” [3]

This will give us the opportunity to clarify the Chinese notion of Shén (神), as well as the Buddhist vision associated with consciousness. For this latter tradition, we’ll be quoting various passages from the Kalachakra Tantra [4][5], which is one of the oldest esoteric texts of the Indo-Tibetan Buddhist world. It’s the equivalent of the Chinese Huang Di Nei Jing, in which the links and interactions between microcosm and macrocosm are explained in detail.

Numbers and names: back to basics

Let’s always start by knowing what we’re talking about, and how to talk about it. This is the principle of Zhèng míng (正名): “the rectification of names”, which we explore throughout our articles. To name something appropriately is already to know it.

We’ll be asking ourselves two simple questions here: why do we speak about “elements”? And why are they always associated with the number 5 and not with 3, 4 or 6? Exploring these two questions will provide us with a good foundation for exploring the richness of the Buddhist and Taoist traditions through their “root” principles.

1) The principle of causality and interdependence between the components of the universe. What are Man and the Cosmos made of, and how do they answer to each other? This is also known as the principle of resonance.

“Sunlight and moonlight are bound to cast a shadow; water and a mirror are bound to produce a reflection; the beat of a drum is bound to be followed by a sound. Thus, every action produces a reaction.”

(Ling Shu, chap.45)

2) The numerological dimensions (3, 4, 5 or 6) in which they can exist. What are the different frameworks and what are their differences?

“It is something I have in my hand and that is felt in the Heart; the mouth is unable to express it; there is an Art (= a number 数) there that stands somewhere.”

(Zhuangzi, chap.13)

Matter or movement?

You’ve probably already realized this if you’ve looked into it, but the term “element” is a translation that conveys a very material bias. In Chinese, the concept of “5 elements” comes from the Chinese term: Wǔ xíng (五行). Wǔ (五) is the number “five”, and Xíng (行) is a verb meaning “to go”. Clearly, very simply, there’s no notion of a material element. The simplest translation, and the one closest to the original meaning, would be “five movements”, which, although less frequently used, seems to me to be a more accurate translation. If the generic term remains the five “movements”, other translations you may come across in books could be :

- The 5 dynamics

- The 5 forces

- The 5 agents

- The 5 breaths

All these movements follow a continuum from the subtlest to the densest, linked by the same system of resonance. In this case, we are talking about a different vibration of these 5 movements. For example :

- The 5 sounds

- The 5 directions

- The 5 colors

- The 5 flavors

On the subject of all these planes of different vibrations, let us quote the Kalachakra tantra:

“The classification of the elements of the body comprises three and a half million distinctions, as numerous as their modifications.”

Kalachakra, stanza 26

Since these variations are so numerous, we are going to be moving forward armed with a sound methodology. Now that we have clarified the notion of element/movement, let’s take a look at their numbers, from 3 to 6, via 4 and 5.

Three 三: the three worlds

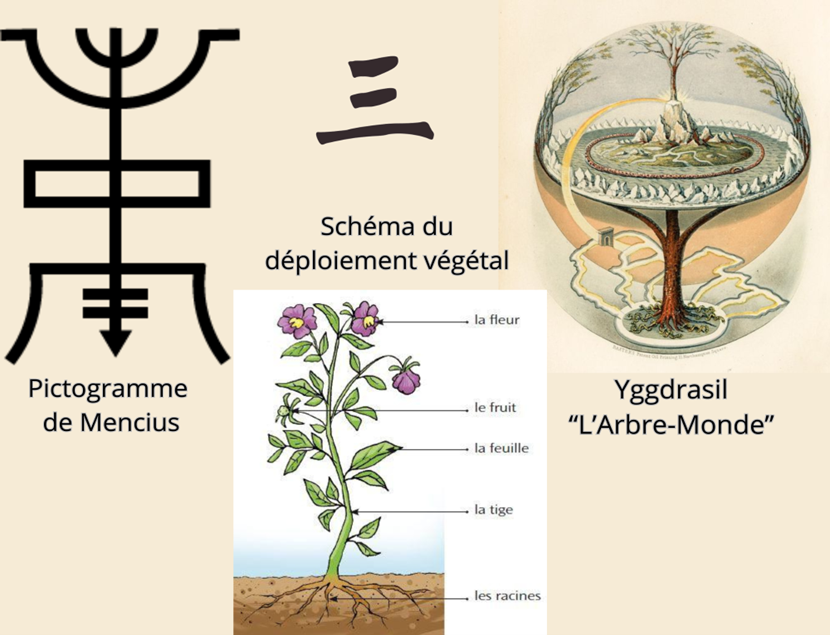

Three symbolises the organisation. In Chinese thought, 3 is the product of 1 and 2, Yin and Yang. Three designates the “3 forces”: Heaven-Man-Earth, symbolically represented by the Mencius pictogram. We also speak of the “3 realms” – the lower, upper and middle – in shamanic traditions, for example.

Three is therefore the 3 main dimensions, or 3 major levels, that organize the cosmos. The tripartition “top, middle and bottom” (上中下, in Chinese: Shàn, zhōng, xià) is a very classic classification that is used in a wide variety of fields.

If we stay with Chinese medicine, the major channels are divided into 3 Yin-3 Yang, and their functions also follow a 3-step model called “Opening, Pivoting and Closing”. Three functions, three dynamics in a 3-stage system. Three evokes the 3 phases of unfolding found in the plant metaphors that abound in classical texts, such as “Root, Stem, Fruit”.

The dimension of Three is the playground (the cosmos) in which movements and elements can play. The geometric figure traditionally associated with 3 is the equilateral triangle.

Four 四: the transition to the Earth

With the number four, we shift into the dimension of Space and Time. It’s on Earth that Heaven brings about changes and transformations. In Chinese tradition, the Wind of the Four Directions (Sì fāng 四方, meaning North-South-East-West) brings about the Four Seasons (Sì shí 四時, meaning Spring-Summer-Autumn-Winter). Through the Four, a movement of ascent (Wood-Fire) and descent (Metal-Water) is organized. These are the main movements that take place in Space.

From each direction (Fāng 方) comes a movement, a particular breath. This is more than a detail, since it’s in this order that the five movements are presented in the first chapters of the Su Wen, for example for Wood:

“The natural green aspect of the eastern quadrant (fang 方)

Penetrates the Liver

Opens its orifice to the eye,

hoards its essences in the Liver,

Its pathological manifestation triggers twitching and jerking;

Its flavor is acid… (etc.)”.

Su Wen, chapter 4

Note that the expression “to open a direction” (chin: Kāi fāng 開方), meant in the classics: “to give a prescription (of a pharmacopoeia)”, or more simply: “to open a therapeutic direction (in space)”. Taking these four cardinal directions, which express the movements of ascent and descent, deployment and recollection, as our primary reference point:

“The four seasons of yin and yang

Are the end and beginning of the Ten Thousand Beings,

The trunk where death and life take root.

Who goes against them,

provokes the catastrophe that destroys his life,

Who follows them,

Prevents all evil,

This is what is called possessing the Way.”

Su Wen, chapter 3

In this passage, we find the plant metaphor of the tree and the metaphor of taking root. Within this fourfold model, it should be noted that everything comes from and returns to the Earth, especially Man:

“By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread, until you return to the Earth, since from it you were taken.”

Genesis (3:19)

This is what the symbolism of the Four teaches us. Earth is the pivot, and it’s Earth that gives the Four its geometric shape, since the square is traditionally used to represent four elements. Think of the 4 elements of Greek tradition (Earth, Water, Fire and Air) from which our zodiac is derived.

One thing that Buddhist and Taoist traditions have in common the importance of Earth as a reference point for the other elements/movements. In China, we would say that the Earth is the Center (Zhōng 中), the 5th direction of the 4 Orientals, the 5th movement of the other four. In India and Tibet, we say that it contains the other elements, that it is the material space that can support and accommodate them. It works hand in hand with another element we discussed at length in our first part: emptiness, space (Kōng 空).

Five 五: from Earth to Space

One of Mankind’s first great crafts is pottery. Pottery enabled semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer populations to gradually settle down, and to store, cook and transport food more efficiently. If you take a closer look, you can see how pottery was one of the first signs that Man had mastered the five elements. Earth is mixed with water, dried by the sun or cooked in a fire, and serves as a container through which air circulates. This tool can be used for a wide variety of different purposes.

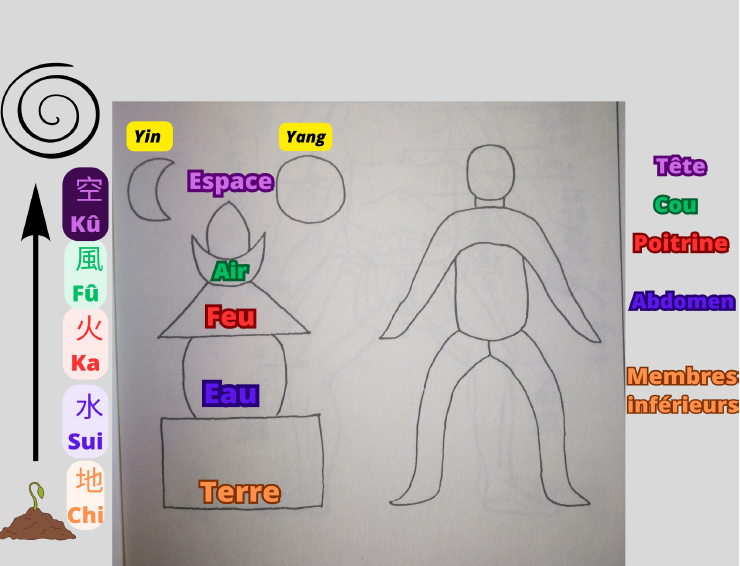

The same applies to the body: everything begins with the materiality of Earth and ends in Space/Vacuity, which in Buddhist tradition represents the 5th element.

Cemeteries in Japan, for example, feature stone statues that combine the symbolic forms of the 5 elements of the Buddhist tradition. In Japanese: chi, sui, ka, fū, kū (Earth, Water, Fire, Air, Vacuity/Space).

The Kalachakra Tantra, states:

“The receptacle and its contents are arranged in sequence, according to their respective natures. (…)

Earth is hardness, Water is fluidity, Fire is heat, Air is movement. (…)

Water, spread over the Earth, is liquid by nature. When we dig, we see it in the Earth. And Space is the receptacle of all the elements: Earth, Water, Fire and Air. As for the elements, starting with Earth, they are the content.”

Stanzas 33 and 18

And how they give rise to each other as dynamic movements and forces:

“Earth gives the seed that lies in the womb’s lotus, then Water makes it germinate. Then Fire gives the blossom and captures the Six Flavours, while Air activates growth. Emptiness provides the space for growth, O Suchandra; this is how the process is accomplished at the appointed times.”

Strophe 4

The Buddhist model clearly shows this unfolding from the densest to the most immaterial, as well as the container-content link between these two poles. Without Earth, there is no container for the other elements (Water, Fire, Air), and without Space, there is no Earth that can be contained. Once again, the bowl is only useful because it is empty.

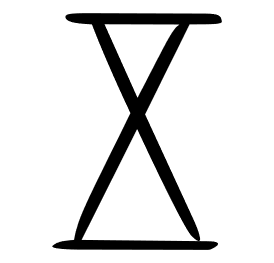

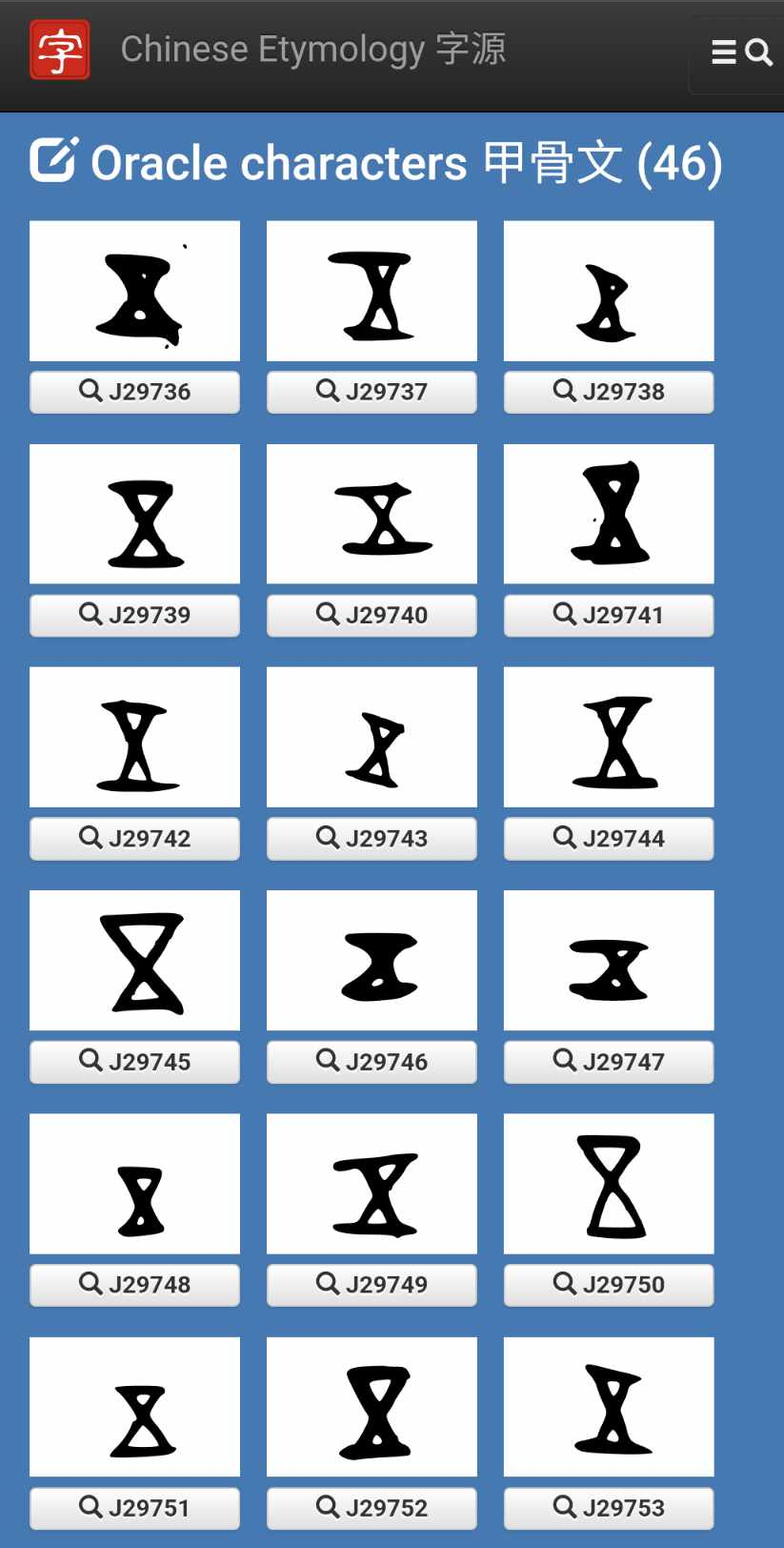

In Chinese tradition, the movement of the five (Wǔ xín ;五行) goes from Heaven to Earth, manifesting itself first in the five notes (or the five sounds: Wǔ yīn ;五音), then in the five colors (Wǔ sè ; 五色). We could place all the manifestations of the 5 movements from the most subtle to the most tangible on the ancient spelling of the character five 「五」, which looks like an hourglass diagram. The hourglass can also be seen as composed of two triangles. Each symbolizing three. 3+3= 6. In terms of directions, if for the Chinese five represents the centre surrounded by the four directions, six brings into Space the notions of up and down (上下): the four orients + Zenith (top) and Nadir (bottom).

In the rest of this article, we’ll see how all these movements create the 6th element. And much more…

(To be continued)

Notes

- [1] Original quote: “Our bodies are made of the burned-out ember of stars that were released in the Galaxy in massive explosions long before gravity pulled them together to form the earth”.

- [2] “Living with the Stars: How the Human Body is Connected to the Life Cycles of the Earth, the Planets, and the Stars”, Karel Schrijver and Iris Schrijver, OUP Oxford, 2015.

- [3] Ling Shu, chap.45, Milsky-Andrès translation

- [4] Meaning “Tantra of the Wheel (Chakra) of Time (Kala)”. The exact date of writing is unknown, but it is thought to have reached Tibet via India around the 1st millennium. A reference text for both yogis and the medical world.

- [5] “Tantra de Kālachakra – Le livre du corps subtil accompagné de son grand commentaire La lumière immaculée”; translation by Sofia Stril-Rever, Ed. Desclée de Brouwer, 2000.

- [6] Kalachakra Tantra, stanza 26, p.116

Glossary

- Wǔ xíng: 五行 (five movements)

- Shàng. zhōng. xià :上.中.下 (top, center, bottom)

- Sì fāng : 四方 (four directions)

- Sì shí: 四時 (four times/seasons)Kāi fāng: 開方 (“to open a direction”)Zhèng míng: 正名 (rectification of names)Tǔ, shuǐ, huǒ, fēng, kōng: 土、水、火、風、空 (Earth, Water, Fire, Air, Space)

Further information

- About the 5 elements in our behavior, voice, expressions, etc.

- “Comment mieux me connaître grâce aux 5 éléments”, Daniel Laurent, 2017, éditions des 5 éléments.

- About hand shape diagnosis according to the 5 elements: “Des planètes et des mains”, Yves Réquéna, éditions de la Maisnie, 1997, Guy Trédaniel.

Author

- The music of consciousness: 空 the Void in all its forms (part 3) - 29 March 2024

- The Five Elements bowl: 空 the Void in all its forms (part 2) - 20 December 2023

- The space within a character: 空 the Void in all its forms (part 1) - 25 September 2023

- Principle : Omote-Ura「表-裏」 - 3 July 2022