Among the many paths we have access to today, we have to admit that many come from Asia. But while the term is increasingly used, it’s not always easy to know exactly what it is. What exactly is a path? And why is Shiatsu included in this field? Here are a few points to help us understand.

With the opening of the world and the circulation of arts, techniques and knowledge, we in the West are now a little more open to the concept of the Way. It must be said that this is not entirely alien to our culture, for in the Middle Ages we also had this concept, but not necessarily under this name. The art of builders (especially of cathedrals), sculptors and blacksmiths, but also that of knights, monks and troubadours, not to mention that of alchemists, all formed paths that could be followed. It must be admitted that today most of these paths have either disappeared or become weaker due to the evolution of industrial techniques and contemporary society.

From the 50s onwards, as the post-war West immersed itself in consumerism as the only path to happiness, a few European and American pioneers brought back ancient wisdoms from India and the Far East, such as yoga, meditation, martial arts, acupuncture… This phenomenon continued to grow, to the point where today we no longer know whether everything we hear and see is an ancient aspect of Eastern culture, or a novelty fabricated for the sake of business.

The difference between technique and Path

Apart from the spiritual Paths, which directly seek to connect with the sacred, the divine, everything generally begins with a technique. Forging, for example, involves removing the slag from the metal and shaping it into the most beautiful object possible. It’s a titanic task, physically demanding, requiring the full attention of the blacksmith. Not too much fire, not too little, the right temperature, sufficient bending of the metal, but not too much either, and so on. But if you take painting, dancing, archery, singing or music, you’ll find just as many constraints and requirements. So, as soon as a technique engages both body and mind, the artist or craftsman is obliged to immerse body, heart, and soul in it if he wishes to achieve excellence. Of course, he or she can also do nothing about it, and simply work without looking for anything more. But as the ancients saw it, a technique remains a technique as long as its sole purpose is to make a living or enrich oneself. On the other hand, if the craftsman sought to perfect his gesture with the aim of achieving a form of perfection in his creation, the technique then became a support to strive towards something greater than the simple product of the work. This is still true today, as it defines the very concept of the “Path”.

Shiatsu also starts out as a technique. As students know, the beginnings are relatively down-to-earth: stretching, pressing, kneading, relaxing and so on. It’s a question of chaining together a certain number of movements (kata) with the aim of producing an effect to improve a person’s physical state. It’s perfectly conceivable that this should remain a manual health technique, which isn’t so bad after all.

So why do the Japanese call it shiatsudo or Shiatsu as a Path?

How do you define a Path?

In the etymological dictionary (Robert), a Way is first and foremost defined by its concrete meaning, i.e. a road, a path. The term comes from the Indo-European Wegh, which in Northern Europe gave rise to Path (English), Weg (German) and in the South to Via (Latin). The Greek root is a little more interesting, as we’re talking about Hodos, which gave us the word Methodos (method). From this, it’s clear that following a Path requires method, rigor and, therefore, teaching. You can’t just invent anything and call yourself a Shiatsu practitioner, for example. You must learn the basics and the principles of the technique, which means that it’s imperative to go through an apprenticeship, often under the guidance of someone more experienced than you. The expressions that use this word are therefore very concrete, such as “get in the way” or “entrer en sa Voie” to mean “to set out”. It wasn’t until the 12th century that the term began to be used figuratively, precisely with the rise of corporations, guilds and other orders of craftsmen who worked with and for the monastic orders and the clergy. This led to expressions like the Narrow Way (the path to Paradise) and the Broad Way (which, conversely, leads to Hell). As a result, the word Way takes on the meaning of “a series of acts directed towards an end”. Given the influence of religion at the time, the Way is the path to enlightenment, to the Divine.

On the other side of the planet, what do the Chinese and Japanese tell us? Early on, they used the character 道 Dao (in Chinese) or Do (in Japanese) to designate the word Path or Way. This character shows the key of the advancing foot or “movement” (辶) surmounted by the term “head” or leader (首). Advancing feet guided by the head can be translated as “thoughts”, but also as “path of thought and body”, which is exactly the Asian way of seeing things. This character was first found on Chinese bronze vases (jīnwén 金文 period, bronze script, Zhou Dynasty 1000-200 BC). Curiously, this typeface is not found before this bronze period, notably during the period of character invention via writing on scales and bone. This means that, from the outset, this typeface was associated with worship, as bronze vases were not used to store water or wine (which would be foul), but rather for sacred ceremonies. The logical conclusion is that, from the outset, the ancient Chinese conceived the term to designate the spiritual path and nothing else. It’s no coincidence that Laozi entitled his work Daodejing (The Way and its Virtues).

The Japanese (among other Asian peoples) made no mistake. While their ancient martial arts ended with the term 術 jutsu (art or technique as in jujutsu 柔術), they transformed their denominations after the Second World War by replacing jutsu with do (Way). The result is what we know today in all dojos as Aikido 合気道 (Way of the Union of Energies), Karatedo 空手道 (Way of the Empty Hand), Iaïdo 居合道 (Way of Life in Harmony), Kendo 剣道 (Way of the Sword), Judo 柔道 (Way of Flexibility), Kyudo 弓道 (Way of the Bow), etc. The same goes for softer arts such as Chado 茶道 (Way of Tea), Shodo 書道 (Way of Calligraphy), Kado 華道 (Way of Flowers). Their aim was to make a semantic transition away from mere technique (too often destructive) towards the Way (spiritual path). So, it’s only logical that the Japanese speak of Shiatsudo (指圧道, the Way of finger pressure).

In the Asian mind, a Way is therefore defined as a personal path via a technique or art. In other words, a Way involves body and mind in the same movement, to achieve a form of perfection. This perfection is often initially the search for the perfect gesture or the perfect object. But for this to happen, the practitioner must purify himself mentally, physically, and emotionally, otherwise he will not be able to achieve what he seeks. This aspect quickly goes beyond the technical realm and becomes an important inner work. This is why Shinto rituals such as Misogi[i] (purification) are important in all Japanese arts and techniques. As with forged metal, this ritual seeks to purify the person of his or her dross, i.e. flaws, bad thoughts, overeating, toxins, negative emotions – in short, to take the person out of his or her comfort zone and encourage him or her to cleanse and rediscover purity from within. This leads us straight to the search for a personal awakening of consciousness. We’re well beyond the realm of mere technique.

Those who walk the Path in the West are also known as “pilgrims”. Since the Middle Ages, pilgrims have worn out their feet and forged their determination over 100s, even thousands of kilometres. Alone with himself, the ego that led him to take to the road in order to prove something to himself, is quickly shattered by the stones of the path and the fatigue of his legs. You could say that pilgrims also shed their skin, peeling off layers and layers to reach the inner light. In fact, pilgrim could be translated as “peel off the kidneys”, a play on words which is quite significant in the light of Chinese medicine since the Kidney is what stores/generates/transforms what’s deepest in the body and energy: Essence (Jing) and primordial Qi (Yuan Qi). All layers must therefore be removed to reach the inner light of the Kidney’s energy, where, according to Taoist alchemy, everything starts and everything returns, everything is transformed between matter and light/energy.

Shiatsu as a Path

Shiatsu is a Path which, like all the others, passes through the experience of the body and gradually wears away the mind, the ego, and the physical body too. You have to feel what it’s like to get up, go to your practice, work on your body, meditate, then listen, touch, massage, press all the people who come day after day, every week, every month, over dozens of years to follow. That’s why we can’t help but respect those who have 30 or 40 years of practice behind them, because it’s an understatement to say that this path is a priesthood. This work wears away our barriers, our judgments, in short, our old skins, which we get rid of to lighten ourselves, to get a clearer feeling, to understand the depth of Qi and the body’s messages, to connect

A parallel can be drawn here with the technique that underpins all the other Paths: meditation. To achieve depth in meditation, three conditions must be met: Immobile, Silent and Aligned (in the present moment if you prefer). It’s in this state that we get our most beautiful moments in life, our mini-satori as I like to call them, and not necessarily during a zazen session. For example, you’re walking in the mountains and the scenery is so beautiful (breathtaking, as the saying goes) that you stop on the side of the road just to contemplate. Your mouth is agape. No need to talk, no need to move just absorb and let yourself go in the grace of the present moment. In this sense, too, Shiatsu has all the ingredients of a beautiful spiritual Path, for we move little, we keep silent, we listen, and sometimes there are real moments of grace, of communion with the patient, but also with the Universe.

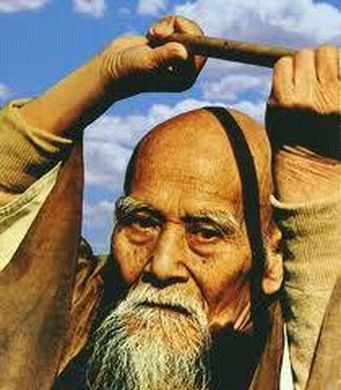

Of course, the technique will give us a hard time, making us doubt, grumble and even despair. But it’s the purpose of all the Paths to test us physically, psychologically, and emotionally. Little by little, year after year, we pass over capes, mountains, desert crossings and inner storms. And there’s plenty of it: loneliness, challenges, terrible doubts, studies that never end, discoveries like lighthouses in the night, mechanical injuries to fingers, wrists, elbows, shoulders, confrontation with suffering, illness and death, but also life coming back, messages from Heaven, inner turmoil, trust in the Universe in spite of everything… and that goes for others as well as yourself. Just as in meditation, you have to stop trying, stop succeeding and, above all, stop forcing yourself. Just let yourself be carried away by the flow of sensations and accept working with what comes, without judgment or impatience. Work on the basics again and again, perfecting your technique, studying your notes, reflecting, starting over, and working again. As O Sensei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido, often said: “Aikido is keiko, keiko and keiko[ii]”. This is true of all the Paths.

As I write these lines, I can’t help but think of the long list of masters who exemplify the Shiatsu as a Path that places us at the service of others, and which – between us – would be better called the “Path of humility and hands”. In the beginning, the practitioner wants results, then later he seeks to shine. Much later still, he drops appearances, keeps silent and gives himself without restriction. Even tsubos and meridians become secondary, and theories fade into the background: what remains is simple, uncluttered presence. The Way teaches us the difference between shining (on the outside, for show) and enlightening (from within, to guide others). This maturation requires effort, endurance, work and time. So give thanks! Thank your patients for being the stones on your path and the masters who are the lamps that light the Way.

Notes

[i] Misogi (禊) is a practice of the Shinto religion whose aim is to remove kegare (impurities) with water, but not exclusively. The term can be translated into French as “lustration”, meaning “ritual purification with water”.

[ii] Keiko (稽古) means “training” and gave rise to the name of the white outfit worn by all Japanese martial artists, the Keikogi (稽古着), literally “training garment”.

Author

- A Milestone: The 2025 ESF Symposium in Brussels - 24 March 2025

- Bosnia – 5-6 April 25: 1st Balkan Shiatsu Summit in Sarajevo - 31 January 2025

- Austria – 19-21 Sept. 25: Shiatsu Summit in Vienna – chronic fatigue, burnout & depression - 19 December 2024

- Terésa Hadland interview: Shiatsu at core - 25 November 2024

- Book review: “Another self” by Cindy Engel - 30 September 2024

- Austria – 24-26 Oct. 25: Master Class in Vienna – Shiatsu and martial arts - 20 August 2024