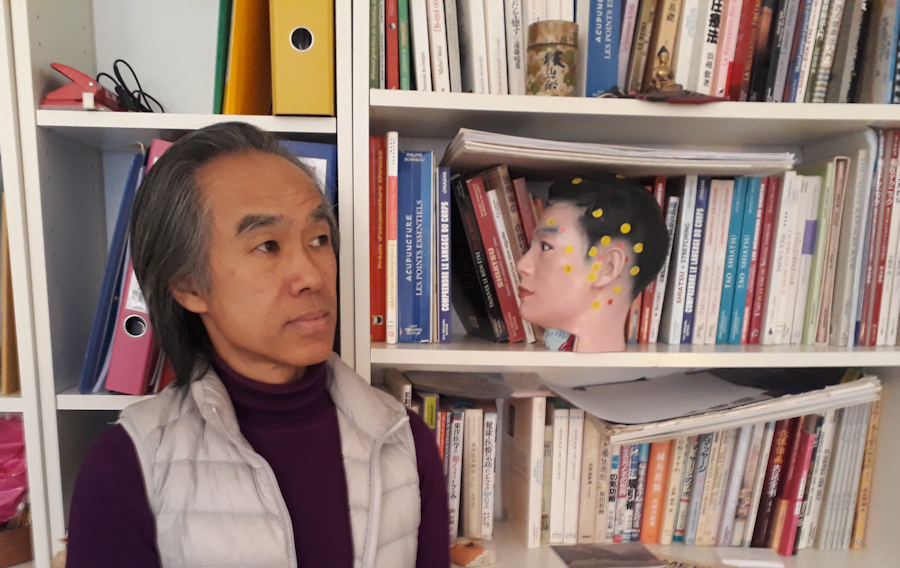

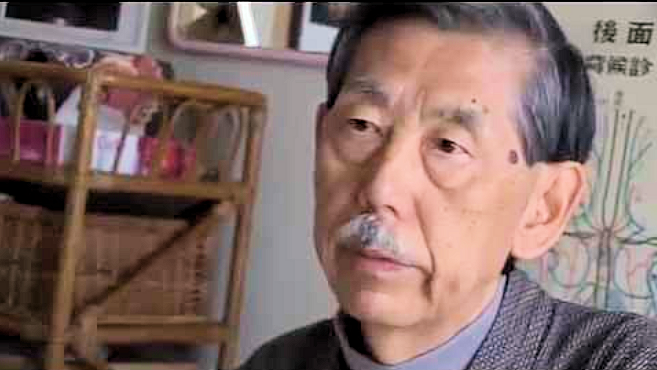

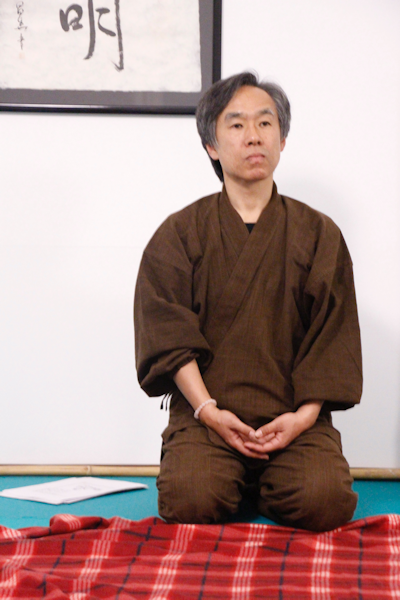

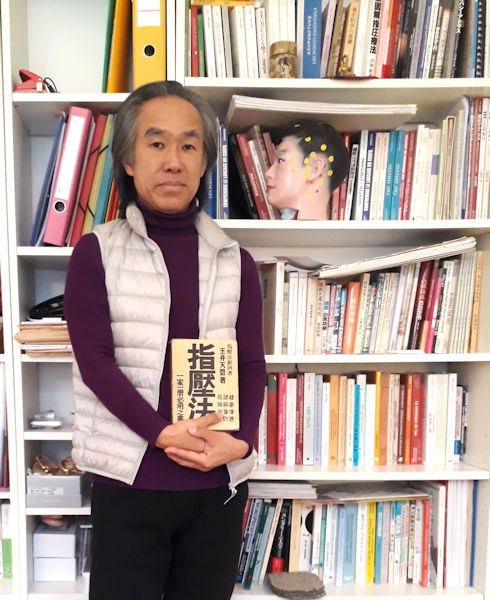

Shiatsu can sometimes guide a person from childhood and only become his or her life path much later in adulthood. That’s the whole personal story of Toshi Ichikawa. Now teaching Toshiatsu in Paris, he is one of the masters who touches people with his simplicity, his books’ knowledge both in Japanese and French and the gentleness with which he expresses himself. I learnt about him the first time thanks to the documentary “The Way of Shiatsu”. Then I went to meet him in his cabinet where a well-filled library was on display. For several hours, we talked about many subjects. Here is his story, his background, his vision of Shiatsu.

Ivan Bel : Hello sensei, thank you for receiving me in your splendid study. Before even starting this interview, I can already say that I love your book collection. First of all, could you tell me where you were born and some words about your family origins?

Toshi Ichikawa: Yes, I was born on October 4, 1961 in the Nakano district of Tokyo. My father, Satoshi (慧) was a constable and my mother, Eiko (栄子), a housewife. They were both born in Yamanashi Prefecture. They met through an arranged marriage and then moved to work in Tokyo.

We lived in a flat located in the Kakoi-Chô district, reserved exclusively for the constables, near the Nakano Police Station. I grew up in this area until I was 10 years old. After that we moved to Hachiôji (八王子), close to the sacred mountain of Takaô-San (高尾山) which is in the countryside around Tokyo. Compared to what you know in Europe, it wasn’t really the countryside, because Tokyo is a very big city and its suburbs are extremely sprawled. My family was quite typical of the 1960s. We were in the middle of an economic boom in Japan, everybody was working hard and was hoping a lot for a better life. I remember when I was a kid the advent of the first washing machine, it was a revolution, even if the clean clothes had to be put into a hand spin-dryer. Television was already there, as well the cars, in short, we were really focused on having a wealthy life.

Toshi Ichikawa with his father…

… and his mother, in the 60’s

So, you can’t say that your family was really traditional.

Partly yes. My grandfather and grandmother, on my father’s side, resided in Yamanashi, near Mount Fuji, and lived in a very traditional agricultural environment. When I was a child, my father left me there every holiday and I had some marvellous time with my grandfather and grandmother. In this rural and agricultural environment, time passed more slowly, everything was revolving around nature and was giving you a sense of being deeply grounded. I loved those regular breaks and I have also inherited this aspect. As you also know, even within modern families in Tokyo, we still live in the traditional Japanese way, characterized for instance by living directly on the tatami mat flooring, folding and unfolding the futon every day, etc.

What is your first souvenir of Shiatsu?

My first memory of Shiatsu goes back to the daily family evenings, when my mother would help my father. I was 5 or 6 years old. My father was in the police motorcycle patrol at that time, but he also walked a lot and did night shifts every three days. This caused him lot of chronic back problems with his back always sore. So every time he came home, my mother and I would do like a family healing. I would massage his feet with my little feet. Then my mother would do moxas, with garlic and ginger.

As you may know, during that time Tokujiro Namikoshi introduced Shiatsu to the Japanese public. My parents regularly followed his TV shows. He talked about everyday things, like the pains that occurred and how to treat them with Shiatsu.

Did Namikoshi had a TV show? I didn’t knew that, that’s interesting. But tell me, what did you study after high school?

I studied international economics. It gave me hope that one day I could get out of Japan. In fact, I was a fan of foreign films and literature. It helped me develop an interest in other cultures from around the world. And I started to dream of leaving my country.

Is this when you decided to become a practitioner?

Since childhood, I had been giving regular Shiatsu sessions around me, to family members, friends, classmates, people who needed it, etc. Naturally, I started to earn money this way, but I never imagined to become a professional. Shiatsu remained my passion for a long time, but I never thought of it as a career.

In high school I was part of the school film club and I was playing in an American football team. During university, in addition to the film club, I belonged to the theatre club. I was very into theatre at that time, because it is at the perfect crossroad between the world of literature and the world of body motion, the usage of the physical body to be itself a performer.

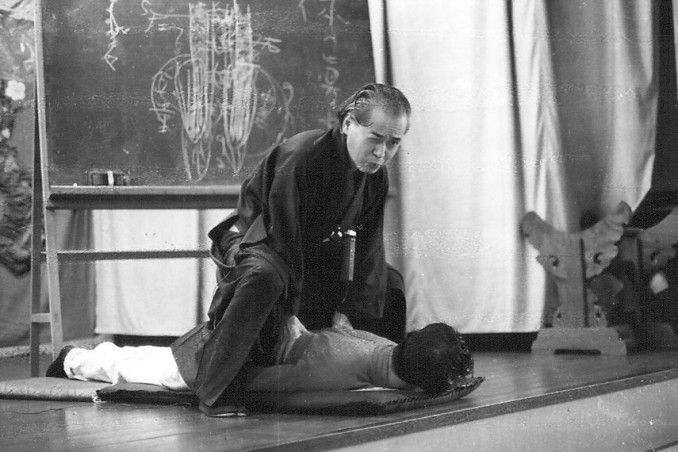

I was thinking of becoming a stage actor, thought which was strengthened as I was surrounded by theatre and movie actors and all kinds of artists. In the 70s, we experimented a lot artistically and I was doing avant-garde body expression and theatrical creation. Our work was very influenced by the approach of Jūrō Kara[i], Shūji Terayama[ii]] and Būto[iii] dance. I loved testing and experimenting my body and this work allowed me create a deeper bond with it, which was very useful for me later on.

And what happened to this desire of leaving your homeland?

While my studies prepared me to become a typical “salary man”, I was living in another world. Eventually I became an employee for a company, which went on bankruptcy the following year. That was a great relief for me, because I was clearly not made for this (laughs). After this experience, I lived on odd jobs and after several years, had put aside enough money to realise my dream, which was to live abroad! But be aware: I wanted to settle somewhere, not travel! I talked about my plans to go abroad and live in a western country and remember everyone was giving me back quite negative feedbacks on this idea.

As I wanted to see Asia, I went to South East Asia and from there to India. Then I travelled to the USA, in New York to be precise, mainly because there were a big Japanese artist’s community and I knew the local art scene well. We were in 1988 and I was 27 years old. I stayed there for two years which changed me completely. But what I didn’t tell you is that my second dream was to become a professional photographer and to achieve this, I started working as an assistant for a photographic studio, and then I became a freelance photographer.

In New York, it’s fantastic! I understand that it transformed you. But as you became a photographer, did you stop practicing Shiatsu?

No, I didn’t stop, but it wasn’t my main activity yet. I was applying what I had learned since childhood. In fact, I had always practised it with artists, or at home with my friends, or with the family. So in reality, I never stopped practicing Shiatsu.

Did you meet Ohashi sensei in New York?

Well…., I thought I needed to learn more about Shiatsu technique, so I went to Ohashi’s Dojo. I was really impressed by the training facility, very luxurious, and when I saw the price, I ran away (laughthers).

What happened next?

In New York, I met a French girl. We left New York to live in Japan as she was passionate about my country. I was still a freelance photographer but, however, continued on giving Shiatsu. To start a serious course, I attended the private lesson of Susumu Kimura sensei, who is still alive by the way. I found it by chance on a small advertisement which spoke about the Kimura Institute in Sasazuka, Tokyo, and as it was not far from my home, I started to go there. We were sometimes 2 or 3 people, not more, it was almost like a private tuition. I really liked his teaching and especially his personality. For me it was the first encounter with a Shiatsu master.

Kimura-san is a very spiritual man. He must have brought a beautiful dimension to his Shiatsu, right?

Yes, we did a lot of meditation and deep breathing work. I was suspicious of anything spiritual at the time; I was not ready. Fortunately, he was very human and efficient in his way of practising Shiatsu. For me this was the real inception into the world of professional Shiatsu.

At the same time, working a lot as a photographer, I felt that my body was starting to wear out. You know, I don’t have a strong constitution and didn’t practice martial arts to strengthen myself. My father, like all policemen, did kendo. When I was a kid, in front of our flat there was a police station and right behind it, a dojo. Kids from the neighbourhood used to go there to train and I myself tried it, but stopped after three months. So, there was no martial arts body workout.

On the other hand, I was drawn to oriental energy disciplines. One day while walking, I saw a small dojo with a large calligraphed sign. A man was teaching Qi gong (editor’s note: Kiko in Japanese) there. I talked with him and he told me about his life, especially that he had cancer and had undergone several operations that didn’t work. So he had given up the “westernized” medical side and started to look for a medical Qi gong healing centre in China where he had been treated and where he learned the technique. He had just opened his dojo and I was almost his first and often, only student. I stayed with him for two years and discovered there what is true energetic work. Then therapeutic Qi gong which is a real deep work that requires doing meaningful introspection. I started after to give treatments in his presence.

At the same time, I joined a traditional method group on the subject of Tanden breathing. This method was called “Tanden Kokyuho” (literally: “Tanden breathing method”). It is one of the “Japanese wellness” arts originating from the Zen tradition. At one time in Japan, in the 1920s and 30s, there were many practitioners of this method, including celebrities from the entertainment, political and business worlds.

Finally, I added the study of Haruchika Noguchi’s Seitai[iv] and Keizo Hashimoto’s Sotai-Hō[v] which was already well known and as well the practice of Mako-Hō which I was using all the time for my back problem.

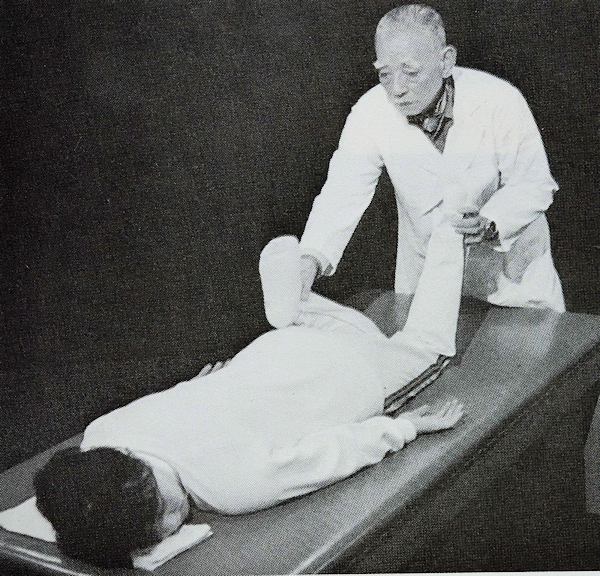

Haruchika Noguchi

Keizo Hashimoto

When you list all the things you have studied, one can say that it is a full background learning process that you were carrying out at this time?

Yes, but I was mainly looking to get out of my unsatisfactory physical and psychological health conditions. All these exercises, all this long-term work that was carrying at that time in my life nourished me enormously. And now, in France, my passion is to share these methods of “Japanese wellness” with Westerners.

How did you come back to France?

I came to France in 1998 with my family and became a photographer. At the same time, I started to learn Shiatsu with Mme Danielle Iwahara-Chevillon [vi] who was a teacher for the FFST and this was like undergoing a second Shiatsu study. She was one of Shizuto Masunaga’s disciples like Kimura-san.

Forgive me, but it is an amusing story to think that a Japanese was trained by a French woman!

Yes, the loop is closed as they say, but I felt it was quite normal that I learn from someone who mastered the subject, isn’t it?

Yes, absolutely, you’re right. And now, in Paris, you are setting up as a practitioner?

No, not yet (laughter).

(laughter) Wait ? But your story is incredible!

It wasn’t still my biggest goal at that time as I wanted to become a talented photographer! But it is true that Shiatsu was taking a more and more important place in my life. I was giving sessions at home, but always in parallel to my work as a photographer.

I felt that I still needed to learn the path of Shiatsu. So I went along with Mr. Yasutaka Hanamura [vii] who lived in Paris and studied with him for two years. He was a very interesting man not belonging to any group or federation. He had his own teaching which was taking place in his flat located in Paris 13th borough and his living room ended up being crowded by way to many people. For the weekend class at his place, it was always concluded on the Sunday evening by a dinner held in a typical Japanese atmosphere.

He was an artist, played classical music, knew well Classical European arts and had a deep knowledge of the culture related to all the subjects which concerned Easterner and Westerner world. His Shiatsu proceeding was very gentle, the opposite of what you find in Japan. Yet, he was dealing with people having severe illnesses, such as cancer. He remained still, listened a lot, and used visualisations. He was paying attention to the patient’s body, but also to his own, to see the interactions, the echo in him. He was an amazing and fascinating master.

Yasutaka-san was also one of Shizuto Masunaga’s disciples. One day, when we were together in Japan, he brought me to the Iokai centre in Tokyo, located in the Ueno district, because I was his only Japanese student at the time. He started to consider me as his disciple so, thanks to this, I was fortunate to meet many people there.

It is also the period when I started reading Masunaga-san’s books in Japanese, especially a little journal that was like a logbook compiling his treatments. By the way, do you know that Shizuto Masunaga wrote many books which, for some of them, are not translated yet? Looking at me reading this book, Yasutaka sensei asked me what it was about and, based on my enthusiasm regarding Masunaga-san’s treatments, wanted me to translate it into French. This is how you found later the French version under the title “Les 100 récits du traitement” [viii].

Thank you for this clarification, because it is a small story which is part of the bigger story of Shiatsu and allows us to understand better what happened. And then, when did you started as a practitioner?

I continued to learn from Yasutaka sensei, especially the Way of Zen Shiatsu, the Shiatsu of Shizuto Masunaga. But my life as a photographer was becoming more and more a bread and butter work, and after a while my passion for Shiatsu started to take over. So I opened myself to the thinking that Shiatsu could finally be my path. I started to read more of Masunaga-san’s books, found that his vision of Shiatsu was fitting well with my life. Unfortunately I never met him as he passed away too early. But thanks to him, Shiatsu has revealed itself as the Way to follow for me.

One day a friend advised me to contact a Japanese practitioner who had been living here in Paris for a long time, Mr. Hiroaki Izumo [ix] so I met him. He wanted to stop his activity and hand over his cabinet next to Montparnasse as well as his clientele. This was an unforeseen bit of luck and incredible opportunity for me and we started by discussing and sharing a lot. So it was a step by step process, and after a year I started to get patient coming in.

When did you start giving classes?

That’s another story. It was thanks to one of my Shiatsu teachers, Mrs Chevillon, who asked me to help her in her teaching and I became her assistant. I started to teach French students and found it quite fascinating. At that precise moment, I really felt I found my place in this country, my role, and since then it has become my path. After this experience as an assistant, I decided to establish my own Shiatsu school in 2010.

Well, what a life! But a rich, interesting life, because finally between Asia, the United States and Europe you have learned and experienced many things, learned how Westerners work, met masters and practitioners of great reputation, passed many tests…

Yes, I’ve been fortunate, and it’s also thanks to all the people which crossed my path.

Do you teach exactly what you have learned?

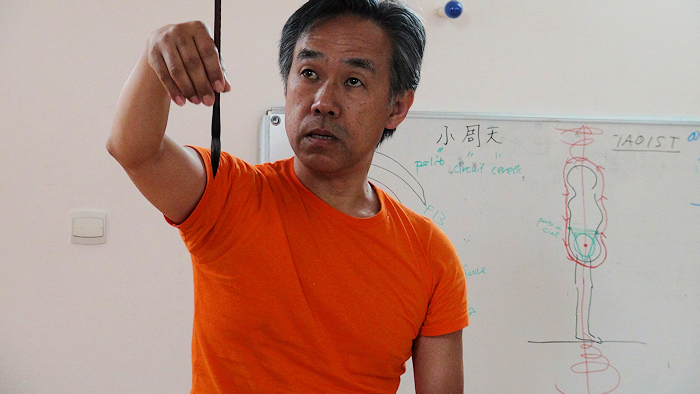

I learned a lot from my teachers as I also learned a lot by myself. By giving Shiatsu, by following my patients, by searching deep inside myself, by reading and crossing views with other disciplines, etc. Today, all that I have learned, all that I am learning, I would like to transmit it to others. That’s why my style is called ToShiatsu, to express a form of Shiatsu which resonate within me.

Your school is called “Do-In”. Why is this?

For me, it is very natural to associate “Do-In” and “Shiatsu”. The two correspond very well. From my view point, you can’t separate them, it’s like Yin and Yang.

The practice of Shiatsu requires a lot of self-control and self-care. We have to be a model for our patients. I use the words “Do-In” in the broader sense of “oriental self-energy work to be done by oneself”.

My way of doing things could be defined as: first the tanden breath! I play Shakuhachi (尺八) [x] which is a traditional Japanese flute used by Zen monks. This instrument requires you to find your breath and body placement at all times, so it is a very good exercise.

I find that the notion of Tanden as one of the most important topics in the Japanese body practice, it must be a core subject in the learning of Shiatsu. In my “腹と腰 – Hara to Koshi” (Belly and Hip) course, I try to share this quest for Tanden in Japanese culture for the Shiatsu practice, until the movement becomes fluidly beautiful. Elegance and style is important in Shiatsu.

I really like this idea of beauty in movement. Tell me more about it. Why is it important that Shiatsu becomes gracefull?

Because “beauty” can change the world and therefore the quality of energy. It can be seen as beauty could transform a life. I’m not only talking about artistic beauty, but also about the sheer beauty of nature, of the living: a river, a tree, a mountain. For me it leads to a kind of change of inner state, but it also impacts the situation of a meridian, of an organ and therefore of a person as a whole. Since I started to identify this concept of “beauty” in my sessions, I finally became an artist. When I manage to create a state of “beauty” in a session, I can feel a great shiver inside the body.

You mentioned a lot about Tanden. How do you approach it?

Be careful, working on the belly is not this relevant, even if, from an anatomical view point, it is obviously important. Especially in its Japanese approach, it is to be considered as an entity in itself, it is the centre which holds the individual personality, its deeper spirit. So it’s of an infinite dimension. Technically speaking, emotions, spiritual awareness, everything goes through it. I am speaking about my personal finding, based on long and thorough studies while I was in Tokyo, this made me understand that the Tanden is the key to many facets of the human being.

When you are in the silence of the practice, and you put your hand on the Tanden, what do you think happens at that moment?

To illustrate this, let me use a Japanese expression: Ittai kan (一体感). The translation in French would give “shared feeling, sensation of two bodies in one mind”. By physically listening to the person, by connecting to him or her, we feel oneness. However, if we mentally analyse, we can distinctly feel the heat, the skin, the tensions, but we no longer create unity. On the other hand, with the unity being achieved, we can feel the internal problems of the person, we can even feel them in ourselves. This is the experience of non-duality. But one also exists for ourselves too, one does not preclude the other. Being one with the other while being one and being oneself. In this way, we can guide the person in his/her depth. Laying your hand on the person is to be a companion, not an energy provider. We listen and this active listening is the help which is needed the most by the person. You don’t necessarily want to remedy all the time.

Shizuto Masunaga often speaks in his books of Genshi kankaku (原始感覚), which can be translated into French as “primitive sensitivity”. It is the understanding that all living things cannot be separated. This is one of the core foundations of Asian philosophy.

As a conclusion to this interview, one last question: How do you consider Shiatsu?

Shiatsu is a path. In the end, through the other person we always try to seek for who we are. This is true at every moment, every day, every year of life. It is an inner quest through the body in search of our essence: physical essence, mental essence and spiritual essence. If we forget to do this search, we transform Shiatsu into a simple technique. We must not let go of ourselves and relentlessly continue to listen to our inner self.

Thank you very much for sharing your journey and your memories. I had a very pleasant time in your company.

Many thanks to you.

Author: Ivan Bel

Translator: François-Remy Monnier

-> Find Toshi Ichikawa on Toshiatsu.com

Notes:

- [i] Kara Jūrō (唐 十郎), whose real name is Ōtsuru Yoshihide (大靏 義英) was born on February 11, 1940 in Tokyo. He is a Japanese actor, playwright and writer.

- [ii] Shūji Terayama (寺山 修司) was born on December 10, 1935 in Hirosaki and died on May 4, 1983, aged only 47. He was a Japanese poet, writer, playwright, sports columnist (specializing in boxing and turf), photographer, screenwriter and director. In his short life, he published over two hundred books and made about twenty films.

- [iii] Butō is a dance that originated in Japan in the 1960s. This “dance of the dark body” breaks with the traditional performing arts of Noh and Kabuki, which seemed powerless to express the new issues of the 1960s, including social upheaval and political crises.

- [iv] Haruchika Noguchi (1911-1976) is the inventor of Seitai, a non-conventional medicine based on the self-healing capacities of the human body.

- [v] Sotai or Sotai-hō (操 体 法 Sōtai-hō) is a Japanese form of muscle or movement therapy, invented by Keizo Hashimoto (1897-1993), a Japanese physician from Sendai. The term So-tai (体) is actually the opposite of the Japanese word for exercise (Tai-so). Dr Hashimoto conceived of Sotai as an antidote to the powerful, regulated exercises of Japan, which anyone could practice easily to restore balance and health.

- [vi] Danielle Iwahara-Chevillon was a student of Shizuto Masunaga for three years in Japan, where she lived from 1973 to 1980. She is the author of “Le Zen Shiatsu et les mouvements intérieurs du corps”, published by Guy Trédaniel, 2009.

- [vii] Yasutaka Hanamura, a disciple of Masunaga, is the French translator of the works of Shizuto Masunaga. He died in December 2017.

- [viii] “Les 100 récits du traitement” by Shizuto Masunaga, translated by Yasutaka Hanamura and Murielle Droux, ed. Le Courrier du livre, 2010,

- [ix] Hiroaki Izumo was one of the pioneers of Shiatsu in France in the 1970s, along with Yuichi Kawada, Tsugo Kagotani, Ryotan Tokuda and others. He was one of Ichikawa’s mentors and often exchanged with him.

- [x] The shakuhachi (or chiba in Chinese) is a straight flute made of a piece of bamboo with five holes.

- FAQs - 12 August 2025

- A Milestone: The 2025 ESF Symposium in Brussels - 24 March 2025

- Terésa Hadland interview: Shiatsu at core - 25 November 2024

- Book review: “Another self” by Cindy Engel - 30 September 2024

- Austria – 24-26 Oct. 25: Master Class in Vienna – Shiatsu and martial arts - 20 August 2024

- Interview with Wilfried Rappenecker: a european vision for Shiatsu - 15 November 2023