As president of the European Shiatsu Federation, Chris McAlister is a personality in the world of Shiatsu. But apart from this official title, we don’t know much about his life and his career. His life is like a novel of travel, adventure, martial arts and oriental medicine, set in Tibet, India, Nepal, China, Japan, England, France and Sweden. What follows is a portrait of a man who spent many years in Asia, traveling and learning with some of the greatest masters of their time.

Ivan Bel: Hello dear Chris. There is something I want to know about your name. You’re living in Uppsala but your family name doesn’t sound at all that Swedish. Where are you from exactly?

Chris McAlister: I am from England and was born to parents born in London, who experienced the second world war as children. I was raised in the suburbs of London, but moved back towards the centre as a young adult. Significantly, apart from the Scots-Irish roots my name implies, my great-grandmother had gypsy blood. I am convinced this has fuelled my wanderlust and curiosity and taken me to the farthest flung reaches of Asia and many other parts of the world.

At the age of 22, I travelled with two friends to India and embarked upon a two-year odyssey that took me through Nepal and Tibet on several occasions. While in Tibet, I became attracted to a wild and exotic woman who turned out – to my surprise – to be Swedish. We travelled together through eastern Tibet by truck, tractor and trailer and even on foot. Gradually we made our way across South eastern China and from there via Hong Kong to Japan. After many comings and goings, we eventually settled here in Sweden, where I still live for a variety of very good reasons.

You’re now President of the European Shiatsu Federation (ESF), taking over from my dear friend Frans Copers. But I’m sure it didn’t all happen at once.

Arriving in Sweden and knowing no one, I was keen to connect and make contacts, especially in the Shiatsu world. I met a few nice people and not only started a school with two of them but was quite quickly accepted onto the board of the association. After a few months I was given the responsibility of helping the Swedish Shiatsu Association to become a member of the ESF. I became the representative and held that post for seven years. I then stepped back and remained in the background to assist the various people who took over after me. After about eight years, it just so happened that the current rep could not attend the upcoming meeting in Athens. Inspecting my schedule, I noticed that I was available and took the chance to step into her shoes.

During a lull in the meeting, I was approached by Frans, whom I had known since my very first days at the ESF – and had invited to teach in Uppsala – to take over after him as president. I was amused, since this was clearly a joke and the very furthest thing from my mind at the time. When the meeting was over, Frans again approached me with the same request, whereupon I realised he was serious. I stepped back mentally to consider the proposition and during the coming days and weeks consulted with everyone close to me on whether or not this might be a feasible and possibly even a good idea. Everyone was supportive and encouraging, and since I did at that time have space for it, I took the post. I reasoned that there was no one else currently available with the same experience or skill set as me, and that if there was a need then I had better fill it.

The first thing I’ve noticed is that you’re a language lover. You speak English, Japanese, Swedish and French. You have also studied in France. How do you relate to languages? And how did you learn them?

I have always loved languages and learned very early on that a language embodies the culture of the people who speak it. When I was 10 years old, my sister moved to Spain for a year and came back a changed creature, speaking a wonderfully exotic language. My brother did something similar a few years later, spending two years in France. I even visited him there and got to see the under belly of Paris – an eye-opening experience for a 15-year-old. I had a talent for French at school and even studied German for four years. This felt like a complete waste of time until I finally moved to Sweden….

I spent a year in France as part of my university degree. I was studying law, which was my father’s idea, but the French minor in European Studies got me a year in Grenoble, near the alps. I wriggled out of the academic studies and spent my time sitting in cafes and making excursions around France and Europe. My French was only mediocre until I met a woman who took me not only to Spain on the back of her motorbike but taught me real French in a variety of situations.

This knack for languages, combined with a talent for mimicry and voice distortion, served me very well on my Asian trip. Speaking conventional English gets you nowhere in Asia. You have to learn to speak their English. My friends thought I was mocking the locals as I modulated my voice to suit their ears. When the results materialised, they quickly changed their minds… I was complemented on many occasions for my excellent “Indian English”.

In China (including Tibet) there are very few English speakers, so it was necessary to learn some rudimentary words and phrases in Chinese and Tibetan. This is always slightly embarrassing and highly comical for the locals, but the doors that swing open make it all worthwhile. Learning Japanese was one of the hardest linguistic challenges – in this language you get nothing for free. Not a word or even a concept is familiar. We all know words like kamikaze, karate and kimono but such words have limited use when you are buying rice and tofu or trying to learn Shiatsu. Japanese is easy in one way – the sounds are simple. The rest is really, really difficult, but I studied hard and practised unrelentingly, and ended up translating a book my acupuncture teacher had put together. This was my next lesson in how Japanese people think – in spirals…!

Arriving in Sweden, I quickly found use for several linguistic threads: German was really useful because Swedish was heavily influenced by it during the Hansa period. More interestingly, I found a use for the hours of tedious study I had endured with Chaucer and Shakesepare as a schoolboy. Old or “Middle” English is derived largely from Germanic, but even more so, Scandinavian roots. With these two free gifts, learning Swedish proved to be a relatively simple exercise.

Learning Chinese characters was also extremely eye-opening, because they show you the foundations of quite abstract concepts. This has been a key insight for me in learning Oriental medicine.

Very early on you were attracted to Asia and I can imagine you taking a backpack and traveling this continent around, let’s say, 25 years old. Tell me how it went? Why in the first place did you want to go there?

In fact, I was 22 when we set out and landed in India. My culture shock was total, mixed as it was with a heavy dose of jetlag. The initial turmoil gradually transformed itself into utter fascination and love, especially for India. My best friend and I had decided to go to India for a year after hearing others’ travellers’ tales. I clearly recall speaking to him from a telephone in the hallway of the student hall overlooking Grenoble. Unfortunately, India had stopped giving unlimited visas to UK citizens and we found ourselves heading for Nepal after only a few months, with the monsoon on our heels. Through a chance meeting in Durbar Square (E.N.: located in Kathmandu, Nepal, which owes its name of darbâr (royal courtroom) to the court held there by the kings of Nepal until 1886), we realised that we could travel to Tibet. (“Where the hell is that?” we all said. “See those mountains up there? On the other side” came the reply). That opened up a world of possibilities and I ended up looping around Asia for another year, before hooking up with my Swedish girlfriend and travelling to Japan.

What was the first experience that marked you in Asia?

The first experience that marked me was brushing my teeth in a very seedy Bombay hotel and seeing 7 gigantic rats running up a drainpipe one after the other. The other major experience was contracting hepatitis in the untamed wilds of Tibet.

Oy my! That must had been a shock for you. So, in 1986, like a lot of travellers in Asia, you were badly ill. But this experience opened up a completely new perception of the world and health. What happened exactly?

I had been continually on the move for 6-7 months by that time, and my health had suffered through a combination of hard conditions and often poor nutrition. I made an excursion to lake Nam-co in Tibet. The lake is three days walk from the main road and I did it with 20 kilos on my back, five on my front and new boots that rubbed my ankles raw. (E.N.: Lake Nam Co or Namtso is 112 Km from Lhasa in North-North-West direction). I was with two Australian girls, who were also headed that way and I began to feel tired on the first day. On the second day I felt slightly worse, but luckily, a bunch of Tibetan nomad riders offered us a lift over the pass with their yaks and horses.

That was wonderful until we arrived at the top and gazed over the landscape towards the distant lake – it was miles away and my fatigue was beginning to set in. After a few hours walking across horribly uneven terrain, I bade the girls go on – I needed to rest and actually fell asleep. Waking up, disorientated, in the middle of nowhere, completely alone, is not an experience I would wish on anyone. Grabbing my things together, I tried to hurry on. After a very scary experience with a massive dog guarding a little Tibetan nomad kid with green snot pouring out of his nose, I struggled on.

Towards twilight I came to a full stop. Ahead of me was only water. As far as I could see in both directions were beautiful colours reflected on deadly still water. Panic set in. I had no tent and not even a sleeping bag. A night in that rugged, open landscape was a thing I did not relish. Luckily, I spotted a tent off in the distance and when I finally arrived, I was greeted by friendly faces – two Aussies and a Kiwi I knew from Lhasa. They welcomed me, gave me food and I stayed warm between their bodies that night.

We arrived – exhausted – the next afternoon at the caves, where we intended to sleep. I collapsed. In the evening, I gathered goat droppings and filled a sack to create a sort of half-length mattress. As night fell, I wrapped myself in my sheet, my blanket and all of my clothes and tried to stay as close to the Aussies as possible. In the dead of night, I awoke, needing to pee. I struggled out of my layers and made it to the opening of the cave, where my breath was stolen away from me. Looking across the vastness of the lake, I could see that snow had come all the way down the mountains at the other end. Cold entered my being. I peed and scrambled back, shivering, into my refuge. In the morning we all made a communal breakfast, which I immediately threw up. Inspecting my skin, one of the Aussies shouted: “he’s got hep”!

I had no medical background, had even ignored biology at school in favour of the new and “exciting” subject of computer science. I was ignorant, bone tired and scared shitless. I sat on a huge rock while the others went “exploring”. Wrapped in my blanket, I contemplated death.

Another night passed, and the next day the party decided to head back to the road. I contemplated three days of arduous travel, knowing that I was in even worse shape than I’d been getting there and that none of the others could provide me with anything more than moral support. Before we left, I decided on a radical course of action. I stripped off and bathed in the ice-cold waters of the lake. Even though the event was shocking, I believe it turned events in my favour. I felt renewed on some level and was – at least psychologically – ready for the task at hand.

We made it back – a truck gave us a lift over the pass and all the way back to the road and the truck stop, where we spent two nights before hitch hiking north. The meal of goat’s meat and greens we prepared at the truck stop was probably the finest food I have ever tasted. I could literally feel how my body was transforming and assimilating the nutrients as I ate and digested.

During the weeks and months that followed, I gradually rebuilt my strength and health. I travelled more slowly, lived more sedately, ate melons and grapes to my heart’s content and dredged up my old football training exercises to renew my physique. It worked. From then on, I began to seek out healers, herbalists and homeopaths whenever I needed any help. Unfortunately, the trip I made a year later (“by truck, tractor and trailer and even on foot”) undid all of this. The conditions we endured during this journey left me once again sorely depleted and wanting no part of anything going on in the world around me.

Several things happened that renewed my energy once again: staying put for two weeks and eating good food on a regular basis; marble tubs full of piping hot water at the bath house; Tuina sessions by a brawny deaf mute in the same bath house and Taiji lessons on the balcony of the hotel from an elegant, elderly gentleman. In two weeks, I managed to completely rebuild my appetite for life: During an impromptu basketball game with some of the local men, I realised: “I’m back!”

Within another two weeks, I had been exposed to acupuncture as well, and from there I never looked back – though I was still far from recognising the path that was being laid out for me.

What a story! Now we’re going to take a little leap in time. Two years later, you decided to start studies in Shiatsu. But why on earth did you start two different schools at the same time?

After my free and easy wanderings in Asia, I was heavily disillusioned on returning to London. Nothing had changed and everything had changed. An aunt of mine later told me I looked like “a fish out of water”. Desperation eventually took hold and I challenged myself and the universe, which led to direct, random discoveries, which in turn led me to Nigel Dawes, who taught Zen Shiatsu at the London College of Shiatsu. We clicked immediately, and after a few months, he had me help him run an open day that the school put on to attract new students. Sitting together afterwards, his colleague said we looked like brothers. That was enormously pleasing and highly flattering for me, of course, but it also says a lot about Nigel’s style of teaching and relating to people – very even and completely without any unnecessary teacher-student hierarchy nonsense. After six months, he told me to go to Japan and study with his teacher, since he was fast running out of material to keep me occupied.

After I had enrolled in Nigels’s foundation course, but before it had started, a friend told me about a woman running adult education classes in Shiatsu. This turned out to be Liz Arundel, and although we never clicked in quite the same way, she was a great teacher and showed me a set of completely different moves and introduced me to the classical acupuncture meridians. I continued with both teachers into their intermediate classes before heading off to Japan.

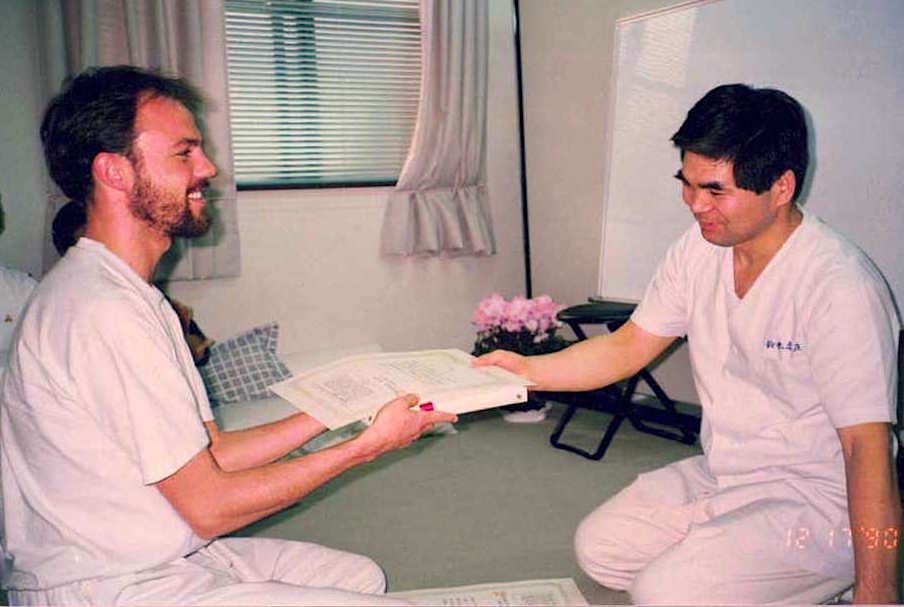

After that, you decided to follow Takeo Suzuki sensei in Japan. How did you meet him?

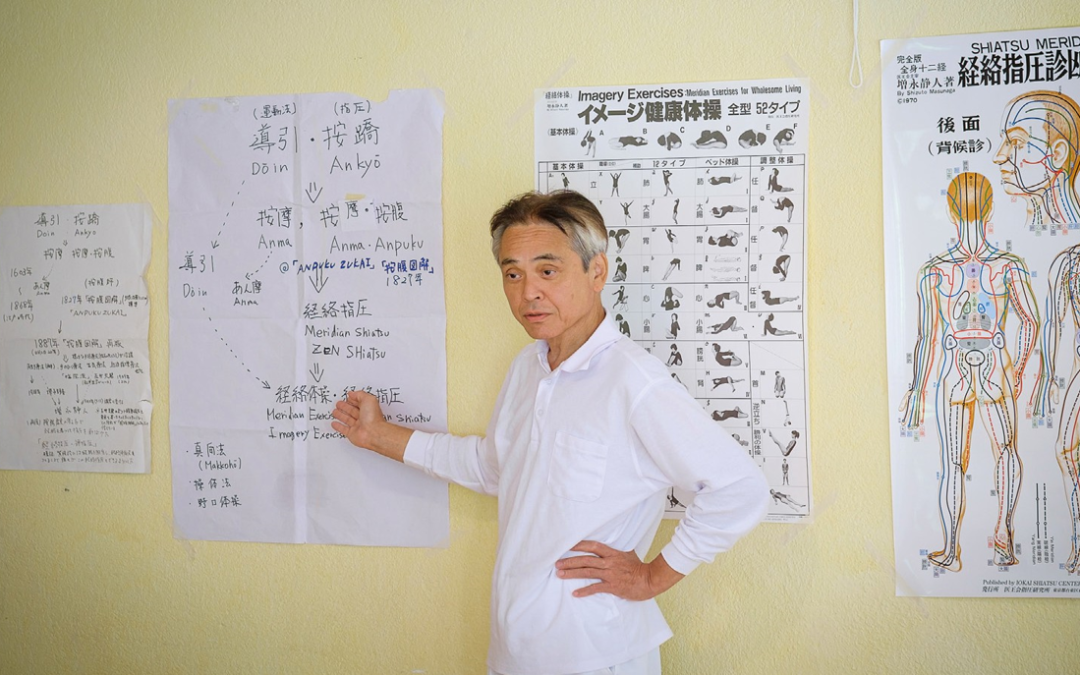

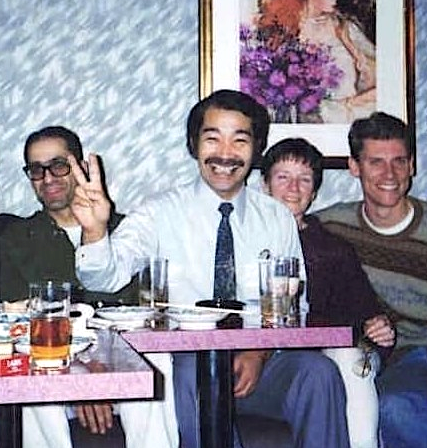

Nigel gave me Suzuki’s name (see Profile #3) but no contact details. Instead he gave me the phone number of his friend, Peter Yates (see Profile #4), who became my Qigong and acupuncture teacher and later martial arts training partner. A stylish and elegant French woman named Cathy took me along to Suzuki’s class, which, at that time, was at his home way on the other side of Tokyo. He took very great care to bring me into line with his approach and iron out all the idiosyncrasies I had picked up during my first six months of study. This was tricky at first, but some friendly guidance from elder brothers and sisters made it possible to knuckle down and get back to basics, Suzuki style. The class was made up of half Japanese and half gaijin – foreigners. A Japanese woman translated and when she left after a few months an American woman took over. Two years later, I had become translator – which was not without its perks.

Suzuki was a very simple man in one sense. He was not given to intellectual or spiritual discussion, was intensely private and, apart from the lessons themselves, wholly uncommunicative. Not very fruitful grounds for a pedagogue, you might think. However, he was a master of Ki and could demonstrate things that I am still light years away from even comprehending, let alone reproducing.

Previously, he had worked at the massive Tsukiji fish market and as a technician maintaining electricity pylons. He came to Masunaga quite late and became one of the favoured students. Stories were circulating among the older students that Masunaga went to Suzuki for treatments at the end of his life. However, his approach to his teacher’s legacy was in some ways less than reverent. He increased the number of meridians (more than two-fold!) and even invented horizontal meridian zones going around the head, trunk and limbs. He experimented with meridian associations to an almost dazzling extent and radically changed the kata. His emphasis was on “release”. If the technique released the flow of ki in the meridians, the technique was good. If it did not, then no matter how beautiful or intriguing a technique was, it was useless and to be discarded. This led to a “bare bones” approach and the kata we learned was therefore simple but very thorough: seated, sides, back and front in classic Iokai style, but shaped by Suzuki’s pared back design. He called it Keitai (meridian-zone) Shiatsu.

I was with him for three years and learned so much it took me another fifteen to make use of even the fraction that I had assimilated. My debt to him is without limit, but our relationship never developed beyond my initial status as golden boy who had come to Japan to study Shiatsu with him, which then soured to one of half-traitor for also pursuing acupuncture and other studies as well.

Did you ever meet Masunaga or do workshops with him?

I never met Masunaga. My relationship with him is as a beloved Grandfather, of whom I have only legend, hearsay, images and two cherished books to connect me. I was given “Zen Shiatsu” as a present during my first brief stay in Japan. It shocked me to read all about my experiences of illness and health, and excited me to realise that I had already taken a few faltering steps on the path he described. Later on, back in London, it was the iconic image on the front cover of this book that led me to Nigel Dawes, my first teacher, via a gigantic poster on the street encountered on my wild and desperate bus ride to destiny. Nigel had studied with Suzuki, who had studied with Masunaga. That book stayed with me and was later complemented by Zen Imagery Exercises.

You didn’t stop with Shiatsu, you also trained in acupuncture.

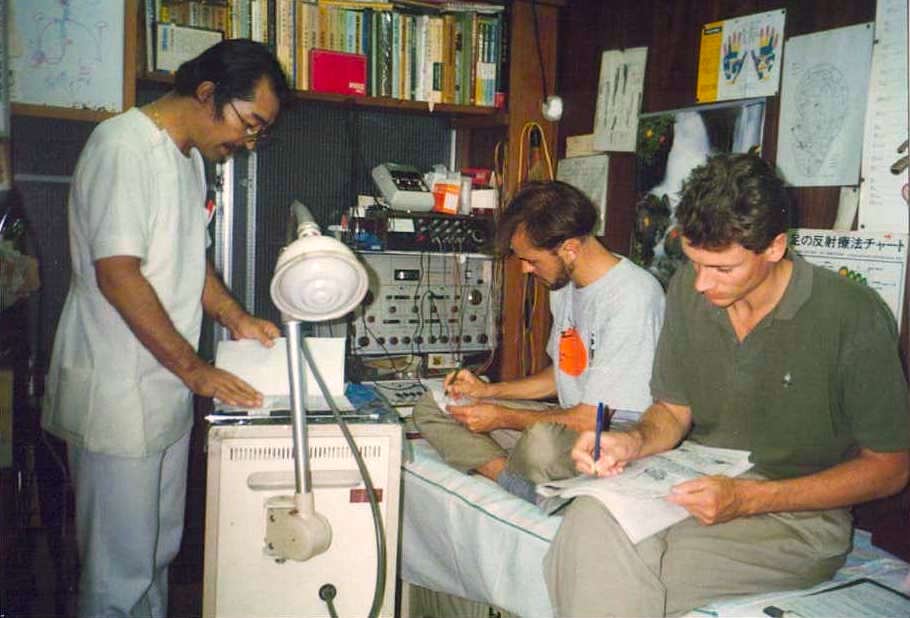

Yes. As I mentioned, Peter Yates was my first contact in Tokyo, and he was just preparing to teach his first ever acupuncture course. He invited me to join, but my budget was extremely limited and I was focused on Shiatsu. However, meeting up with him again a week or so later, he not only started teaching me Qigong but connected me with both a Taiji and a yoga teacher. We happened to go out dancing after a visit to the yoga teacher in question and hit it off like two old friends on the dance floor, imitating monkeys and other beasts of the imagination. I spent the night in his girlfriend’s spare room and after breakfast the next morning he once again asked me to join his class. I repeated my pathetic mantra: no money, focus on Shiatsu, whereupon he invited me to take the class for free. I was stunned and surprised, and asked him why. This was quite a lot of money, after all. His reply was two-fold: “Because I think you’ll be good at it and because I want you in my class”.

The deal was done. After the first term, I paid my way, of course, and after two years we travelled to China to study in Guangzhou (Canton) with twelve other students. Peter also introduced me to Gotoh Sensei (see Profile #2), who was then my acupuncture teacher for another three years in Japan.

Your love for Asia doesn’t stop at Japan. You went on to be an uchi-deshi in Canton, China at a martial art school. Please tell us more about that period of your life that spreads from 1990 to 95.

Peter had made a new friend in Tokyo – Greg Winder – a lovely man from New Zealand. Everyone liked Greg – he was easy going and a lot of fun to be around. He’d studied both Chinese and Japanese martial arts and had some beautiful Qigong forms, which Peter set him up teaching. They talked martial arts, senseis and sifus and became so close that Greg invited him, together with two other friends, to travel to Canton and study with his teacher: Wa Guo (see Profile #5). I was not included in that trip but half a year later, after studying some Choy Li Fut gongfu [I] with Greg, I was allowed to accompany him.

We stayed one month with Wa Guo and it was like being in a martial arts movie: Up at dawn to stand in the semi-darkness in deep horse stance. Breakfast together then morning practice. After lunch practice resumed. We learned two very dynamic but highly contrasting forms: Loka Bafa, a combination of Taiji, Xingyi and Bagua, and a spear set from the traditionally female Yang family.

One year later, I was back there with Peter for an altogether less exotic and far more gruelling month of pure Xing yi quan [II] fundamentals, spiced with some Taiji, Hung Gar [III] and Shaolin two-man forms – for light relief! A year after that, we returned for part two of the Xing yi journey. This time it was just as gruelling but also more rewarding as we learnt six of the Xingyi animal forms, a combined Xing yi form called Endless Returning, a two-man Xing yi set, and a Xing yi sabre form.

These experiences are engrained on my soul and in the very marrow of my bones. Never have I suffered so much but also laughed so hard. Never again have I had to endure smells and substances emanating from the core of my being and endure sleepless nights stretched out, seemingly electrocuted, on a wire camping bed that felt more like a torture trestle.

The Chen style of Taijiquan is very different from Yang style because it retains the ability to do fast and offensive movements like traditional Gongfu styles. I can imagine that it was a hard training.

This is true. The story goes that the Yang style came about when master Yang, who practised the Chen style, was asked to teach members of the Chinese royal family. He eliminated much that was arduous and demanding, opting instead for elegance and flow. Yang style still contains countless martial aspects and is deadly in the hands of an expert. However, the Chen style looks far more like a martial art, even though it is traditionally performed slowly – at least at foundational levels.

My Taiji journey started with a modern, hybrid form in the hills of Dali, South-West China (E.N.: Yunnan province). It continued with a Yang 108-movement form, learnt with Ray Wilkie in Clapham, South London, then progressed through Ichi Raku An, a Taiwanese hybrid style (from Taiwan) in Tokyo with Koida sensei. Finally, I was brought into contact with Chen Pei Shan, 20th generation lineage holder of the small frame Chen family style. I studied with him for a year or two before leaving Tokyo, where he still lives and teaches. I have met him only once since then – at a seminar in Paris, but have also trained with his top European student, Dietmar Stubenbaum in Friedrichshafen, Germany.

Chen style Taiji is not for the faint-hearted. It requires at least one year merely to complete the outer form. From there, one re-commences the programme, this time learning how to make the movements deeper, more fluid, relaxed and continuous. The next time one starts the programme, the emphasis is on bringing the movements from the core of one’s being. This process continues and may in time result in the student learning the much faster canon fist form – a scary thing to watch.

Do you agree with this proposition: martial arts and healing arts are two sides of the same coin?

Yes. Having said that, it must be said that very few modern martial arts proponents would even recognise this as being an interesting let alone a viable proposition. The same goes for many involved in the healing arts, especially in the West. Nevertheless, from time immemorial these two have been two sides of the same coin. One traditional argument is that if you learn to destroy, you must also be able to heal and repair the damage you have caused. That seems like a reasonable request to me.

In Japan you started studying and working in an acupuncture clinic in Yokohama. My question is simple: how did you manage to study all those things at the same time and in different countries?

In Japan it is very difficult, logistically, to remain there for any longer period of time. You have to leave the country to renew your visa – at least every six months. Many of my trips to China and Korea were planned for this express purpose, and of course to allow studies with other teachers.

The other major factor was my mindset. I was not interested in a career as an English teacher – this was only to pay my bills and fund my studies. My priorities were clear: studies first, work as little as possible to finance them. Luckily, English teachers in Japan were well paid at that time and the jobs I retained were the pick of the crop. Working only six to seven hours a week I could live – frugally – and pay for my studies. This gift is rare and I appreciated it thoroughly for the time it was available.

I suppose the other major factor is that I met people who were willing to help me and provide me with even more contacts to assist me further on my way. This kind of generosity is important – it demonstrates that people are essentially kind and will always help if you ask with the right attitude.

After those years in Japan and China, when you came back in Europe you were certainly fit and strong. But were you already familiar with moving Ki?

As I mentioned, Suzuki’s method was a “bare bones” one, where the only truly essential ingredient was the ability to release ki. If you could not do that, your technique – and all your strivings – were pointless. This I was able to transpose into Qigong and acupuncture and even in certain of my martial arts practices. I also had the very good fortune to meet a true living treasure – master S.K. Lew. (See details about him in Profile #1, at the end of the interview).

As a boy, Sifu Lew lived and trained at a Daoist temple in Southern China, before emigrating as a young man to the USA. Peter and a friend of his, David Brickler, would bring master Lew to Tokyo every year and during my five years there I met and trained with him five times. The very first thing I learned was a long, quiet internal set called Shen Gong. Part standing and part seated, it is an almost entirely static programme that induces a massive amount of internal ki movement.

All of these experiences, if practised continuously, leave one in no doubt that touch, combined with openness and intention can move ki in a myriad ways.

Fantastic! By the way, I notice that you studied Chinese herbs with Ted Kaptchuk in Amsterdam for two years. How was that?

Ted (see Profile #6) was an enormously influential teacher on many levels. Coming back to Europe and settling in Sweden, I had to start from scratch again. I reasoned that studying with such a renowned teacher would inevitably be both rewarding in itself and a great networking opportunity. It was – in ways I am still counting. Firstly, it gave me the chance to meet up with my friend from Tokyo, Nik Kyriacou, who now runs the school we started our training at, the London College of Shiatsu. Every two to three months we met in Amsterdam and swapped stories, while co-translating Gotoh Sensei’s book.

Ted himself is an enigmatic and intriguing character. Many know his book, The Web that has no Weaver, which I had read but did not impress me. Thankfully, he wasted no time in calling the text a very rude name and never mentioned it again. Ted went from being a researcher of research methodology, via 20 years of intense immersion in Chinese medicine, to researching placebo at Harvard University. From this, we realise that we are dealing with a truly unconventional individual.

After the first day of class with Ted, I was stunned. After many years of solid study, I felt I knew nothing. What then ensued was a journey through concepts, stories and legends going all the way back into the mists of barely recorded medical history, tracked wherever possible with references. He introduced us to the individual herbs, giving us full descriptions of their characters and with what kind of people or situations we might have use of their abilities. This was followed by the formulas, where this process was repeated. Finally we dealt with clinical situations where we might employ these various formulas, case studies and in-the-flesh diagnosis practice sessions.

Once again, I felt stripped to the bone and rebuilt in a new way with a more interesting, nutrition-filled flesh. I lost touch with Ted immediately the course finished, but still feel him with me at times as his stories light up my treatment sessions or teaching moments.

This is an incredible journey I must say. Then in 1996 you went to live in Uppsala, Sweden. What happened that made you decide to go and settle there?

I was sitting on a train, coming back from Narita airport after the second trip to Canton with Peter. The Tokyo skyline appeared, and my heart rebelled. Next day, out walking with my girlfriend, I sheepishly confessed that I was done with Tokyo and Japan. To my amazement, she said she had just been waiting for me to say the word. We looked at our options. Neither of us wanted to go to England or the UK. I was all for jetting off to New York, but she vetoed that and instead suggested Sweden. I had visited Sweden twice previously – in the summer – and enjoyed the space, fresh air and high skies. What is more, my chosen studies and would-be career had partly been chosen from the perspective of being able to pursue them anywhere in the world, so I agreed.

Looking at your journey, I see that you have always taken responsibility upon yourself: In 96, co-director of SAOM school of Shiatsu in Stockholm, director of Isshin Gakkai school (Shiatsu and oriental medicine) in Uppsala, Qigong instructor in Uppsala prison, Personnel stress manager in Uppsala Hospital, in 99 leader of advanced acupuncture students in Canton, Qigong and Shiatsu instructor in Jerusalem and so on. It’s a really busy life!

Well, yes and no. Anyone who knows me will tell you that I enjoy kicking back and doing nothing, enjoying a meal or a glass or two glasses of whatever is being offered. I love to travel and can sit still for hours if I have a good book to read, good company and tranquil setting – ideally all three. I really enjoy writing and am involved with several book projects, one of them a very comprehensive look at Oriental philosophy and medicine through the lenses I have been exposed to over the past 30 years.

During my teens, I read the books of Carlos Castaneda, which had a major influence on my life. Carlos’ teacher Don Juan repeatedly admonishes his adept that there is no time – you need to act now. The samurai code, another huge influence, is famous for reinforcing the same message – death is just over your shoulder. You may not wake up tomorrow, so you have no time to lose.

On the other hand, we are well aware of the message encoded in the phrase “wu wei”…

Thats true and I also know how hard and rewarding it is to stick to the wu wei. You’re at the same time the president of the European Shiatsu Federation (ESF) since 2013, and of the European Federation for Alternative and Complementary Medicine (EFCAM), since 2019. This makes you the most influential and knowledgeable person on these topics on our continent. Can you describe the situation of natural health in Europe and the position of Shiatsu in this set?

That may not be entirely accurate. My personal philosophy is grounded on the realisation that I, in fact, know very little and am therefore reliant on others who know more. I have around me a group of experts who know all about their own countries and their own fields of knowledge. As president of the ESF, I have a clear understanding of my role, which is dictated by my own personality as much as external circumstances. I am not a born leader but have been called on to lead at various times of my life – something I am happy to do, so long as I have the full support of those I am “leading”.

The ESF has a 25-year history behind it and it is a fairly turbulent one. National associations have come and gone. Personalities have left their mark and disappeared. When I shouldered the Presidency, my first task was to restore internal harmony and then to consider external matters. This I have done. The current group of representatives is a wonderful and thoroughly harmonious one, which I am very proud to be the leader of. During the seven years of my time, we have gradually extended energy outwards to heal old wounds and create new alliances. This is moving in very encouraging directions, one of them being eastwards – the Hungarian Shiatsu association recently joined the ESF, and we are hoping to visit the membership in Budapest next year.

Our major push at this time, however, involves what is called the EQF: European Qualifications Framework (read the article on that subject). Very briefly, this is an EU initiative designed to create equivalency between academic professions and the more hands-on professions. The ideology behind it is to raise the status of non-intellectual trades, where Shiatsu comes in very nicely. The central idea is to turn know-how, gained through training and experience, into formally acknowledged qualifications. This has been achieved to a certain level by the SPS in France, and the Austrian Shiatsu Association, the ÖDS, is now attempting the same feat at an even higher level – bachelor’s degree. Once three associations have achieved this, a European profession will be established according to the guidelines of the EQF, at least at the level of education.

As far as the wider field of complementary medicine (CAM) goes, there is unfortunately at this time very little unity. There still exists a potentially disastrous split between medical and non-medical practitioner groups, which prevents the field from properly unifying. There is also the ever-present spectre of the medical establishment, backed by huge lobbying forces, which watches our every move and frequently intervenes to frustrate both group and individual CAM-oriented initiatives. The current “crisis” has demonstrated precisely how precarious our position is – we have received a very clear message that our work is still considered “non-essential”. There is a lot of work to do.

At the outset of my Presidency, the ESF decided to pull away from the CAM arena as part of its main strategy and focus instead on our right to freely practise our profession throughout the EU. This right is embodied in several EU founding treaties but has never been enacted as law in any single member nation. What this means in practice is that even though practitioners in Austria and France have some degree of formal legal recognition, they cannot take this with them into any other EU member state – in clear contradiction to the founding treaties and the spirit of free movement contained within them.

This is the basis of current ESF policy. Taken together with the EQF initiative, we believe that we have the stepping stones to establish a Shiatsu profession – regulated by professionals for professionals.

Looking back now, did you imagine your life was going to be like this?

No, naturally, I had no idea my life would turn out like this. My father wanted me to be a professional football player, whilst my mother saw me as a ballet dancer. I turned out to be a Taiji and Qigong instructor, which I feel is a fair compromise. At various times in my life I have leaned towards being a translator, a musician, a bohemian with no discernible career path and now some kind of writer.

One thing life has taught me is that nothing is predictable and that, as the Yijing says: change is the only constant. I have seen my life move from phase to phase, sometimes against my will and sometimes in tune with that will. I believe the skill lies in sensing which way things are turning and not resist but to adjust and try to flow as best one can with the changing conditions as they appear.

My personal motto has become: Expect Nothing. Expect Everything. Who knows what the future will bring? All we can do is prepare and be prepared.

Thanks so much for sharing all these memories. It’s been a real pleasure listening to you.

My pleasure.

Information:

In September 2020, Chris McAlister will be in the coming European Shiatsu Congress: https://www.europeanshiatsucongress.eu/trainers/chris-mcalister/

Notes:

- [I] Choy Lee Fut or Choy lay fut or Califo (pinyin: càilǐ fó quán; meaning “Buddha Càilǐ boxing”) is a Chinese martial art from Guangdong developed in the nineteenth century. Founded in 1836 by Chang Heung (1806-1875).

- [II] Xing Yi Quan is classified as one of the internal styles of Chinese martial arts. The name of the art translates approximately to “Form-Intention Fist”, or “Shape-Will Fist”. The earliest written records of Xing Yi can be traced to the 18th century, and are attributed to Ma Xueli of Henan Province and Dai Long Bang of Shanxi Province. Legend credits the creation of Xing Yi to renowned Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD) general Yue Fei, but this is disputed.

- [III] Hung Gar, Hung Kuen, or Hung Ga Kuen is a southern Chinese martial art belonging to the southern shaolin styles. It is associated with the Cantonese folk hero Wong Fei Hung, a Hung Gar master. Hung Gar’s earliest beginnings have been traced to the 17th century in southern China. More specifically, legend has it that a Shaolin monk, Jee Sin Sim See (”sim see” = zen teacher) was at the heart of Hung Gar’s emergence. Jee Sin Sim See was alive during a time of fighting in the Qing Dynasty.

Book:

- “Touching the Invisible: Exploring the Way of Shiatsu” Chris McAlister, Jeremy Halpin & Jan Nevelius, Authorhouse UK, 2021

Profiles:

1- S. K. Lew – last of a generation, master of Qigong, martial arts and Daoist healing

Minimalist skill was Sifu Lew’s signum: he lived to the age of 97 and was active as a teacher and healer virtually until his dying day, so the lesson seems to be one worth learning.

Sifu S. K. Lew was 75 years old when I first met him in Tokyo to study a form called Shen Gong. I had never met anyone like him before and was very taken by his presence. He moved with extra quietness, as though the air was slightly padded around him. He didn’t talk much and only looked around in a very sparing fashion.

He looked pretty old as well, with his white, stringy beard, but that’s when I learned that appearances can be deceptive. He was accompanied by his wife, Juanita, and their 8 year old daughter. Joking around with her, he suddenly dropped like a stone into a low fighting stance that stilled my heart and took my breath away.

As a homeless boy, Sifu Lew and a friend had asked a monk selling herbs in the village square whether they could go back to his temple with him. The monk agreed, and so began Sifu’s stay at the Yellow Dragon Temple on Buddha Mountain in Southern China’s Guangdong province. The friend only lasted a year or two, but Sifu stayed. He learned martial arts, healing arts and, in time, the full Dao Ahn Pai Qigong and meditation system.

My favourite story involved his main teacher. One morning, Sifu was on his way to the meditation hall when they ran into each other. They exchanged a few words and Sifu walked on, leaving his teacher behind. Imagine Sifu’s surprise when, on entering the hall, he saw his teacher already seated, deep in meditation. At this point in the story, Sifu paused and looked around at the group, a delighted smile twinkling in his eyes. He says to me: “maybe you never understand what happen here today”.

I also studied Six Stars, Five Breaths, Earth Meditation and a Qigong healing practice from the extensive curriculum. Sifu passed peacefully a few years ago, leaving the lineage firmly in the capable hands of Juanita Lew, who is now the unquestionable holder of a tradition that traces its roots back to Liu Dong Bing, one of the legendary Daoist Immortals.

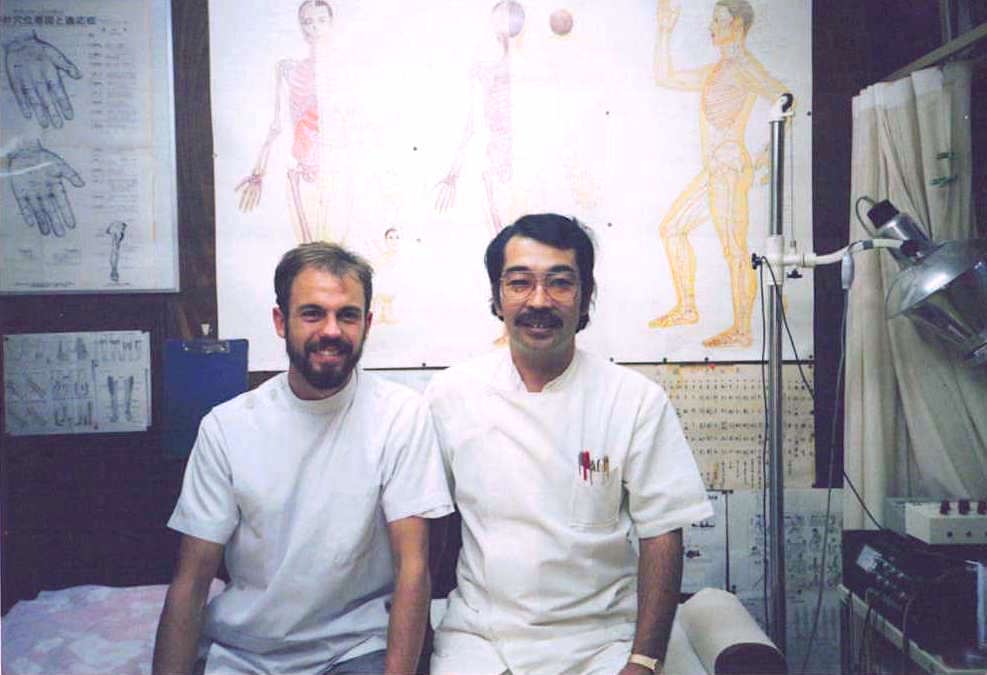

2- Gotoh Kimia – chiropractor, master of Ryodoraku, modern Japanese hybrid acupuncture, bon vivant

Gotoh Sensei was one of those people you call “larger than life”. For a Japanese person, he was exceptionally large in all aspects of body and soul. He loved his coffee extra strong, his saké extra dry and his cigarettes extra long. He had only the most rudimentary of skills in English but made maximum use of them.

He had hands like a bear and simply laying them on you impelled immediate and complete surrender. Generosity was second nature to him and he invariably erred on the side of giving too much – never the other way. He reminded me of the large-bellied buddha, with the eternal smile.

Gotoh sensei had been a pharmaceuticals salesman, travelling around selling legal drugs to doctors. Sickening of this, he had gone back to school and come out a trained chiropractor. Encountering the equally charismatic Dr. Oiso on his travels, he started learning a peculiarly modern Japanese hybrid acupuncture called Ryodoraku.

Ryo-do-raku, meaning “connectivity channels”, is the brainchild of a certain Dr. Nakatani, who created a system of diagnosis and treatment using acupuncture, wired to very mild electrical current, and resting on the physiological model of the autonomic nervous system for its theoretical foundation.

His patients treated him like a cross between a family doctor and a slightly bohemian village elder. His prices were not very high and people would just leave a small wad of notes on his table as they shouted out their goodbyes on leaving. No need to check, no need to book the next treatment – come and go as you please. Feel at home – trust and relaxed intimacy.

What sensei taught me above all else was to be as natural as possible with the people who turn up for treatment. They’re just people who are suffering for one reason or another, and they can do without you sitting on a high horse and quoting scripture at them, thank you very much.

Peter Yates once said of him that he was an example of a truly healthy man – there was something essentially life-affirming in everything he did.

And he was an absolute expert at Ryodoraku acupuncture, a true master craftsman.

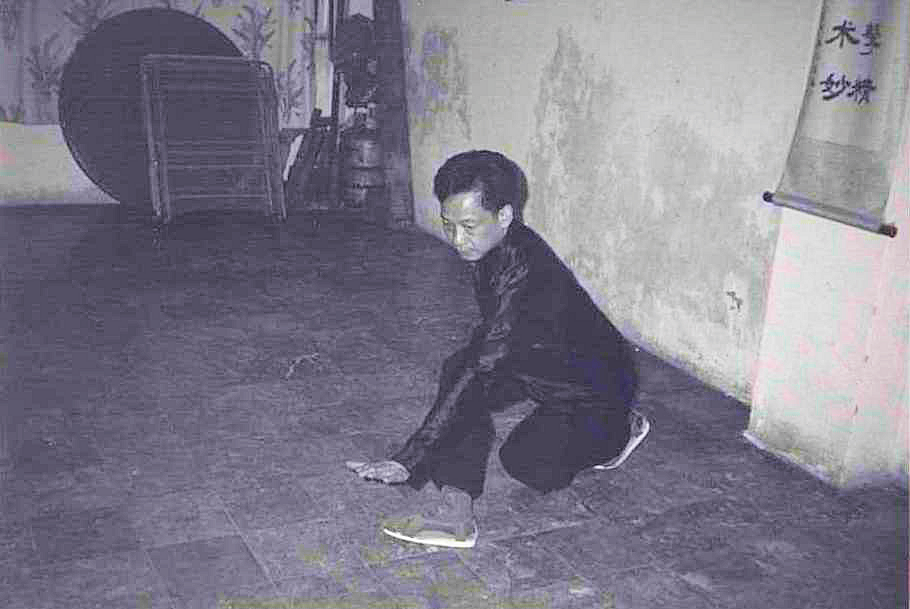

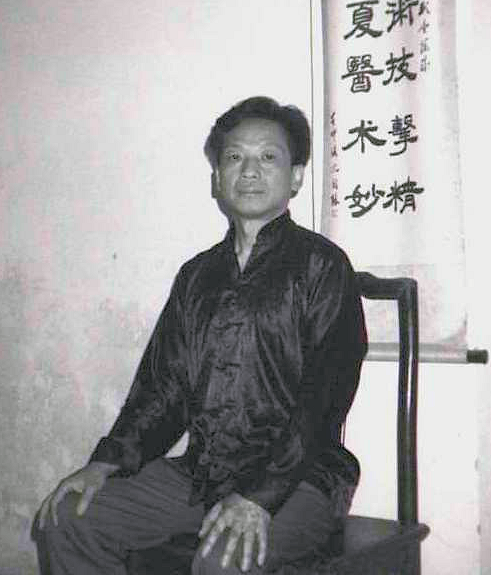

3- Suzuki Takeo – Shiatsu master, eccentric genius, Qi expert

Takeo Suzuki was my main Shiatsu teacher. He had been a student of the legendary Shiatsu innovator Shizuto Masunaga. Their relationship had been close – when the master found himself staring serious illness and death in the face, he entrusted himself to his Suzuki’s capable hands.

As with all disciples of charismatic innovators, Suzuki followed his own path from the moment of his master’s death. His research and innovatory changes to the basic design maintained at the Iokai Shiatsu Centre, led to parting of the ways and he struck out on his own – a controversial course of action in Japan.

When I met him, he was established as an independent teacher with a small and devoted following equally divided between Japanese and students of other nationalities.

His method was to first simplify everything to its essence. This he did with the “kata” he had inherited from Masunaga. The form he taught was simple, with far less emphasis on elbows and knees and a much softer, smoother approach then Masunaga’s. This was done to facilitate energy sensing, which in turn was designed to make energy interaction during Shiatsu treatments as efficient as possible.

We spent hours and hours perfecting our pressure, posture and touch. His morning classes were circular – once we had practised the four positions (seated, side, back and front) we would take a short break and then simply start over from scratch.

The simple wisdom of this method lay in the sheer repetition and the gradual deepening of the student’s familiarity with the external movements, leading to a greater appreciation – and eventual mastery – of the internal aspects of the practice.

The afternoon classes were the exact opposite, however. Yes, we devoted hours and hours to palpating the hara in the quest for the perfect diagnosis technique. However, the afternoons were also his arena for presenting ideas and techniques from his own research.

Everything was research for Suzuki: He presented a scheme of how the 14 main meridians affected the various anatomical and functional aspects of the eye; he explained how the various meridians were connected to elemental and environmental aspects of life; he developed his own system of facial diagnosis; he presented new ideas on how deep deficiency (in-kyo) could be accessed and treated, the detection and release of inflammation, at least twice as many meridian pathways as Masunaga and meridian-based cross-zones that ran around the body in sets of 14 in the arms, legs, trunk, neck and head. He even taught us a new sequence for the five elements…!

As a practical researcher and modulator of energy, Suzuki is still unsurpassed in my experience. He showed me beyond any doubt that energy is not only real and palpable, but also susceptible to direct interaction on many levels and through many channels – not least touch. He instilled in me an independence of thought, that has legitimised my own attempts to understand, to discover and to create. He left me with a hundred unresolved issues – some of which still crop up in new guises even today and lead to interesting discoveries in Shiatsu and energy work.

I used to receive news of him from students whom I had introduced to his class, but one day someone reported that his clinic was gone and that he and his family had disappeared without trace. Suzuki had previously worked at Tsukiji fish market. He had also been employed as a telegraph pole technician. For a while he had been a Shiatsu therapist and teacher – something of a master, in fact. Perhaps it was simply time for a new twist on this lovably eccentric man’s life path.

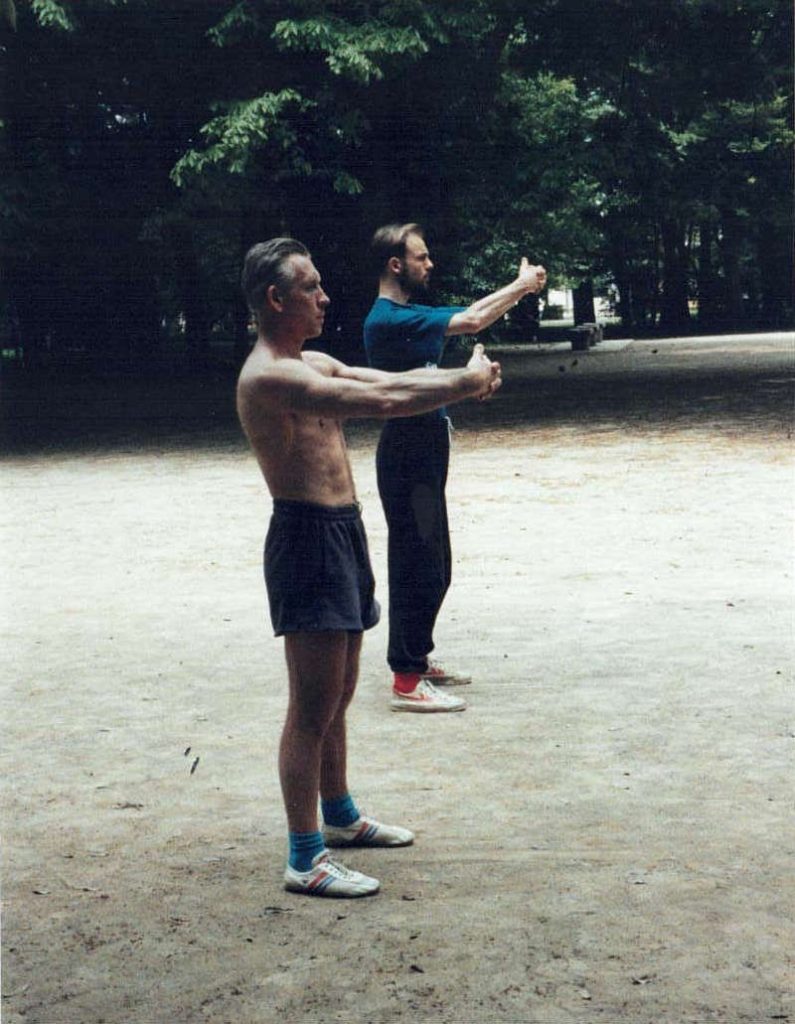

4- Peter Yates – autodidact, strongman, gentle giant, scholar-sage

My first meeting with Peter was all shock and awe. His impressive frame was ripplingly muscular. Atop the sculpture sat a hugely smiling face and a broad Lancashire accent.

Pete immediately fixed me up with an excellent Shiatsu contact, a yoga teacher and a Taiji teacher. In the weeks that followed, he also became my Qigong and acupuncture teacher. For the next half year, I met up with him and a bunch of rag-tag students in Yoyogi park to practice Qigong twice a week – rain or shine – for which I paid a very modest amount.

The acupuncture class – his first ever – he gave me for free. Why? Because we had connected, because he thought I’d be good at it and because he wanted me in his class. Simple as that.

Pete led a bunch of us to China for intensive acupuncture studies and he also set me up with Gotoh Sensei, my next acupuncture teacher. A year later we reconnected to start the next phase of our mutual development, practising martial arts both at home in Tokyo and in Canton, China with a genuine master of the martial arts.

During my five years in Tokyo and in the 25 years since then, Pete has taught me many things:

- Pass it on! You can’t keep it, so give it away and the next phase will come to meet you.

- Teacher and student is not a one-way relationship. If a teacher can learn from his students, both develop in ways no one could have foreseen.

- Be yourself. Whatever you are exposed to, whichever roads you take, whoever you come in contact with, always remember who you are. Pete came from extremely humble origins – a mining town in Northern England, where prospects were either “down the pit” or nothing much. He has been on the edge of trouble several times in his life, but always been humble enough to take good advice and a way forward when it was offered.

Later in life, Pete has returned to his roots – strength training according to old-time strong man traditions, and Northern Soul dance. These are important for Pete and help him return again and again to renewed vitality as he follows his life path of Qigong, martial arts and acupuncture.

Pete has been to Sweden four times to teach my students. I have been to the US a few times to teach his. Always there is the spirit of free exchange, mutual learning and then kicking back in total ridiculousness to relax and return to the path with renewed joy and vigour.

He is and has been a living inspiration to thousands of people and a model of how to live a life with modest but proudly upright self respect. I count myself lucky to have become one of his friends.

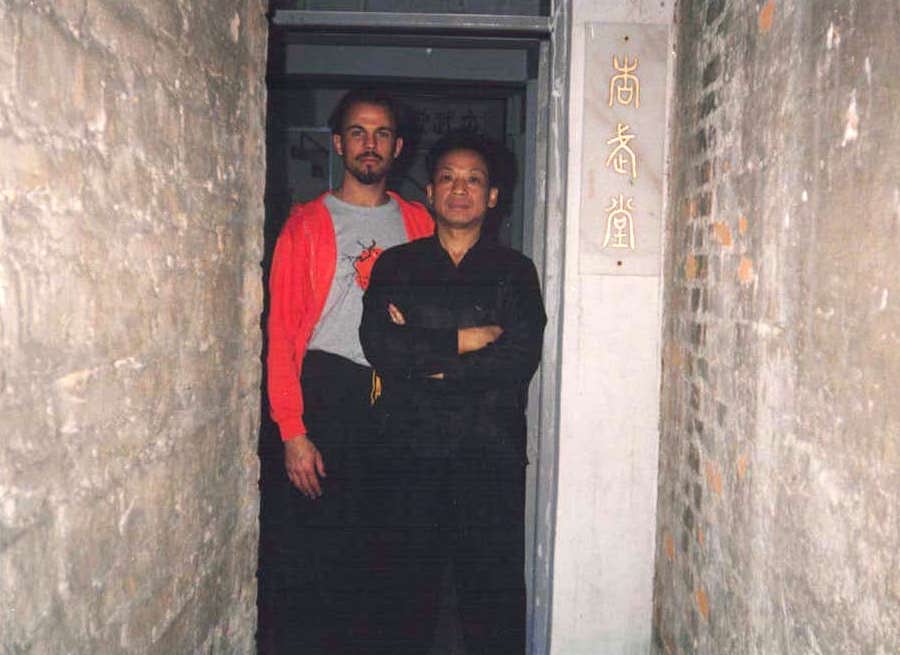

5- Wa Guo – martial artist, calligrapher, bonesetter, Oriental medicine practitioner

Wa Guo was everything you could ask for; the real deal – a master of both Chinese medicine and martial arts. Several martial arts. Many martial arts, as it turned out.

We stayed in his house, in the back alleys of Canton. We got up at dawn, assembled in the dojo (his downstairs room) and stood in a low horse position for forty minutes in the half-light. After breakfast, we studied a form that combined the three internal martial arts – Taiji, Xingyi and Bagua for three hours, then had lunch together.

In the afternoons we practised a spear form from the Yang family. Although the thrusting, jabbing, twisting and leaping were arduous and complex, we had a great time. We learned a few supplementary exercises, but those were the two main forms we took home with us and diligently practised for a year and a day.

Next time was completely different. Just me and Pete. And Wa Guo. And Xing Yi. Pete had specifically requested this, and I had agreed – blissfully unaware of what awaited me. Training started next morning. We were to hold a fiendishly painful position for thirty minutes. Kindly, Wa Guo let us know that the 30 minutes could take up to an hour. We could rest and resume as often as we liked, but 30 minutes of real time were required. It was pure torture.

Wa Guo came home for lunch. We’d put on a brave face. In the afternoons the real pain started. Wa Guo had told us that the key words to keep in mind were “fixed and unchanging” – thoughtfully, he’d underlined them in a dictionary for our benefit. We kicked off with a deep posture from hell. Also 30 minutes. This time, no breaks. We could however switch sides as often as we liked. We changed sides so frequently, he didn’t even have time to correct our stances properly.

Then came movements; difficult, precise movements, incorporating this position of pure pain. After a couple of hours, when he was satisfied that we were half dead, he took us through some two-man Shaolin forms and Taiji push hands routines: just for fun – just to loosen up. We didn’t sleep for a month.

Wa Guo plagued me with corrections – mostly for my very inelegant posture – but his manner was faultlessly polite to the end. The thoughts and emotions ricocheting around inside me were far less so. Believe it or not, we went back for more the next year. We even learned a truly wonderful Xing Yi sabre form, as well as six of the Xing Yi animal forms, including the punishingly explosive dragon.

Returning to Canton in 1999 with a group of my own acupuncture students, I was able to fulfill my ambition to learn a drunken style Gong Fu, practising once more on the hard tiles of his downstairs ”dojo”, this time with Gong Fu brother and acupuncture student, Martin Thambert.

Sifu Guo passed away two years ago in 2018.

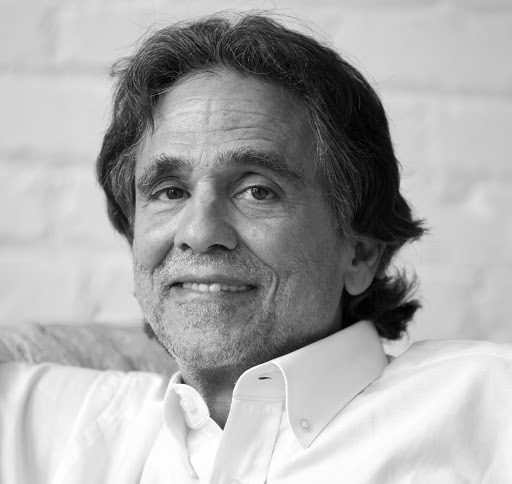

6- Ted Kaptchuk – esoteric scholar and researcher

Studying Chinese herbs with Ted Kaptchuk in the late 1990’s was a life-changing experience.

During our very first lesson Ted named and summarily dismissed his own famous book in one sentence. He then informed us that the Nei Jing, the seminal text of Chinese medicine, was a “polemical text”. Most of us were shocked all the way out to the tips of our toes and all the way into the marrow of our spine, but in fact he was being polite. It turned out that what he meant was a propaganda text, one intended to sweep away an old paradigm and usher in a new one. Years later, having sampled the therapeutic gems of antiquity which did not survive into the Nei Jing’s revised cosmology of Yin-Yang and the Five Elements, let alone into the post-revolutionary TCM system, I can appreciate what he was trying to say.

And that was just for starters. Everything I had learnt about Oriental medicine during the ten years leading up to that point was suddenly cast into doubt. Ted told us that he was going to hypnotise us and teach us not what to think but how to think. He would, he said, provide us with syntax and grammar and invite us to write our own sentences. All of these promises he then proceeded to fulfill.

One of Ted’s teaching mantras during the two years of the course was: “I’ll teach you what the herbs do. You make up the symptoms.” Taken at face value this may sound outrageous, irresponsible, anarchic, absurd and even meaningless. As with all masters, he was speaking in code.

As the course developed, we began, slowly, to understand the encoded meaning of his words. What he intended to do was teach us all about the energetic actions of the herbs. What does this mean? It came to mean a description of the herb’s character, personality, movement and direction. In particular, of course, we needed to know which meridian or meridians the herb was most closely associated with. Once we had understood this, we knew what the herb did and once we knew that we could begin to employ it.

Working backwards from clinical situations we could easily identify which herb or, more often, formula would best fit the situation at hand. This is what he meant by “making up the symptoms”.

Consider the wisdom of his approach. Another teacher might have given us an abstract list of symptoms a given herb or formula was reputed to address. Such a list is almost impossible for the average student to remember beyond the end-of-term test. If on the other hand, we came to know the herbs as energetic beings with clearly described personalities, we would remember them in a completely different way – they would come to life.

Ted subsequently returned to his academic roots and is currently engaged in placebo research at Harvard University.

- Book review: “Another self” by Cindy Engel - 30 September 2024

- 24-26 October 2025: Master Class in Vienna (Austria) – Shiatsu and martial arts - 20 August 2024

- Lembrun Summer Intensive Course – July 6 to 12, 2025: Digestive System Disorders, Advanced Organ Anatomy, and Nutrition - 4 August 2024

- Anpuku Workshop with Ivan Bel in London – 7 & 8th, June 2025 - 22 June 2024

- Interview with Wilfried Rappenecker: a european vision for Shiatsu - 15 November 2023

- Interview : Manabu Watanabe, founder of Shyuyou Shiatsu - 30 October 2023