In 2017 an exciting conference was held about traditional Shiatsu vs modern Shiatsu took place, at the Shiatsu European Congress [1]. The purpose of the discussion was to highlight the differences between the roots and the evolutions of Shiatsu nowadays and whether there is a tradition in Shiatsu or not. When pondering the question, even as a long time practitioner, the answer is not clear. Yet there is a tradition in Shiatsu. Let’s delve into details.

Around the world, schools or styles declare themselves traditional Shiatsu. But to the question “what is tradition?”, one generally gets either an embarrassed silence or a reference to the Namikoshi school, all others being only derivations and later developments. But Tokujiro Namikoshi was not the first to practice digitopressure in Japan. During the conference in Vienna, the debate had a hard time finding out what tradition in Shiatsu is and answering these specific questions:

- When does tradition begin?

- How does one define tradition from a technical point of view?

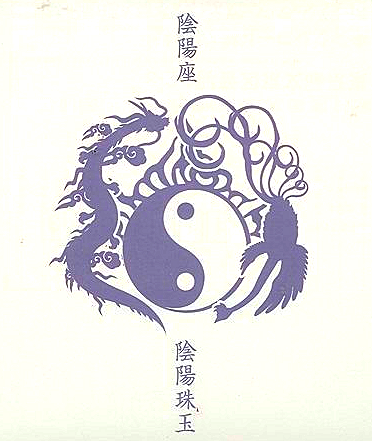

Only Bill Palmer deemed that the tradition that was dear to him went back to Chinese Taoism and the notion of Wu Wei (non-action) and that Shiatsu today tended to forget that one should not force the body of the patient. The tendency is to do manipulative therapy (as in physiotherapy), instead of accompanying the individual in his path of transformation. One can actually trace the philosophical and theoretical tradition back to Taoism, where we find all the theories that underlie the art of Shiatsu (Yin-Yang, Earth-Man-Sky, and so on). However, Shiatsu has many roots.

Historical roots

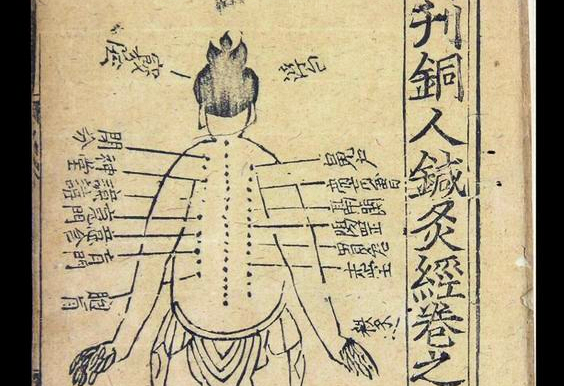

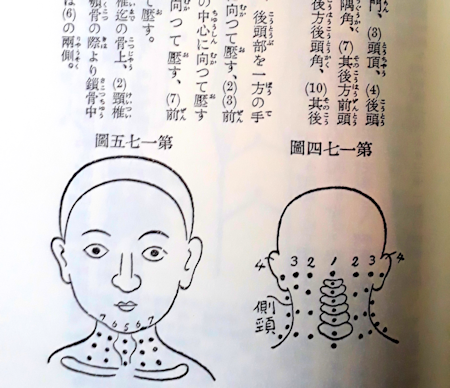

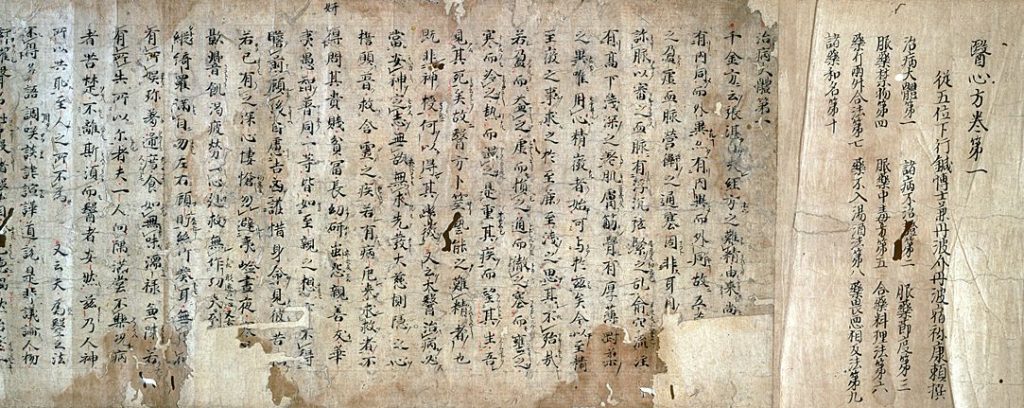

Without going back to the Chinese roots (since 1120 BC) of the Anmo-Tuina, Japan adopted since the fifth century in its history the Anma massage, since the first exchanges with the continent. But very quickly, the Japanese ingeniousness embraced this technique to transform and enrich it with new contributions. In 718 the first medical academy opened its doors, sponsored by the government of the time, to study acupuncture. But it was also possible to become “Jugonshi” (呪 禁 師, i.e. spellcasting therapist) or “Anmashi” (按摩師, massage therapist). This took three full years of study and also included the study of bandages / dressings and the repositioning of bones and joints. In 984 Yasuyori Tamba wrote the first medical book ever written in Japanese, Ishinpō (医 心 方). It covers all areas of the medical world, including Anma.

In the Edo period (1602-1868), the capital moved from Kyoto to Edo (Tokyo) and classical Japanese culture reached its peak. The arrival of Westerners changed the medical landscape and the Japanese opened up to anatomy and physiology. Acupuncture and Anma were first taught to the Dutch who had been trading since the end of the Portuguese presence, then it was the turn of the Americans, French, English and Germans. At that time, the blind people were allowed to practice Anma. Their practice was described as Genko Anma (relaxation massage) compared to the therapeutic version called Koho Anma (古法 按摩). In that time, two important books appeared:

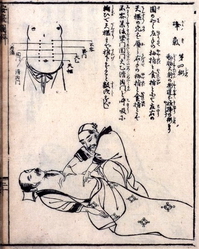

- In 1827, “Anpuku Zukai” (按 腹 圖解) by Shinsai Ōta, Yoshikoto Murata and Ryōsai Urabe is the book that compiles all the techniques of belly massage from the Anma.

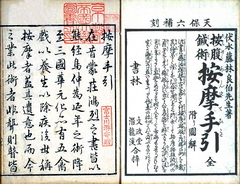

- In 1835, “Anma Tebiki” (按摩 手 引) by Fujibayashi Ryohaku who tries to save all the memory of the Anma massage.

The first book is often regarded as the work of inspiration of Shiatsu and the second is the one that allowed the creation of the school of Anma Fujibayashi Ryu (藤 林 流 按摩). All the official schools that followed flowed from this first school. They are called:

Sugiyama Ryu Anma (杉山 流 按摩) founded by Sugiyama Waichi

Yoshida Ryu Anma (吉田 流 按摩) founded by Yoshida Hisashi

Minagawa Ryu Anma (皆 川流 按摩) founded by Minagawa (?)

In the Meiji era (1868-1912), shoguns gave way to the imperialists and Western influence failed to completely eliminate the traditional arts, especially in the medical field. The therapeutic dimension and Chinese medicine completely vanished from Anma massage and Western physiotherapy took first place in the minds of Japanese as the only form of effective massage. It was a dark age for all the Japanese traditions. However, in an effort to recover the knowledge of the past and the art of healing, two books will be released during the Showa era (1926-1989):

- In 1934, “Inyō gogyō setsu” (陰陽 五行 說, meaning Yin / Yang and the 5 Elements), by Tadao Iijima, in an attempt to bring Chinese theories back to the fore.

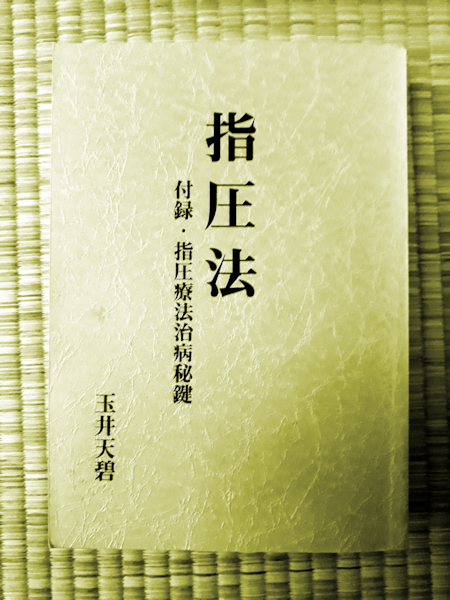

- In 1939 “Shiatsu Ryoho” (指 圧 療法, Therapeutic Shiatsu Method), Tenpeki Tamai, which integrates the Western notions of anatomy and physiology and which takes up all the part of the therapeutic Anma.

Tenpeki Tamai is the founder and inventor of the term Shiatsu and it is from this date that the term will be repeated by Tokujiro Namikoshi, Dr. Hirata for example and many others thereafter. His work is of course based on previous publications.

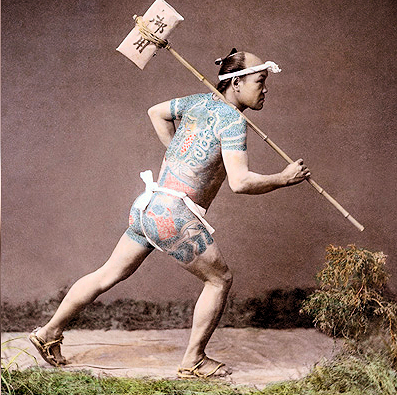

Cultural roots

As we have just seen, Shiatsu is not a creation ex nihilo, but the result of a historical evolution. But Japanese culture has also strongly put its mark on Shiatsu. This is seen first in the postures that are those of everyday life as Seiza (sitting on a tatami) or the martial world as tateiza (a foot flat and sitting on the back foot) that serves to draw a sword.

The world of martial arts, but also that of arts and crafts still uses the same body shape and the same movements. Take a calligrapher. He does not move his arm to draw a character on his leaf, but koshi (hips). In Ikebana we do not bend to pick a flower, but we bend the hips. To plane a board in traditional carpentry, one does not twist the back, but one always places the hands in front of the hara, the hips well opened, so as not to spoil the lumbar. Everything is codified in the Japanese art world and the body responds to this codification. This traditional heritage of the use of the body explains why in Shiatsu one does not bend, one does not twist the back and that the postures as well as the mechanical movement are precise.

And again we must consider ourselves happy, because part of the bodily tradition does not apply to Shiatsu as salvation, etiquette and the way of walking. For this last one must be aware that until the 19th century the Namba aruki march was de rigueur. It was a matter of walking with the arms still on the sides of the body, or with the hand and foot together on the same side and not crossing as we do in the West. This way of walking allowed to always keep an available hand to draw the katana. In the dojos the walk is done by pointing the foot forward and putting first the forefoot and then the heel afterwards. Again, we are doing the opposite.

Technical roots

If historically and physically there are Shiatsu roots, it is now obvious that the Shiatsu technique is itself a tradition. There are 10 technical parts in the Anma, you will recognize them for having probably already practiced:

- Keisatsu Ho (軽 擦 法): light tapping technique also known as Anbu Ho (按 撫 法)

- Kyosatsu Ho (強 擦 法): technique of rotation & friction with good pressure also known as Annetsu Ho (按 捏 法) which one finds more in the Ampuku part.

- Junen Ho (柔 念 法): kneading technique also known as Junetsu Ho (柔 捏 法)

- Appaku Ho (圧 迫 法): pressure technique

- Shinsen Ho (振 せ 法): vibration technique that contains two branches

- Gaishin (外 振): external vibration

- Naishin (内 振): internal vibration

- Haaku Ho (把握 法): grasping and tightening technique (not used in shiatsu)

- Koda Ho (卯 打法): hard percussion technique (used in kuatsu)

- Kyokute Ho (曲 手法): melodious soft percussion technique with folded hand

- Undo Ho (運動 法): Movements, stretches and rehabilitation from the Do-in Ankyo which is composed of 5 branches:

- Jido Undo Ho (自動 運動 法): Individual movements combined with equipment

- Tado Undo Ho (他 動 運動 法): Movements aided by the therapist

- Shincho Undo Ho (伸张 運動 法): method of stretching

- Teiko Undo Ho (抵抗 運動 法): Endurance tests, physical exercises and body resistance

- Kyosei Ho (矯正 法): Structural diagnosis of bone and joint adjustment methods

- Kenbiki Ho (腱 引 法): rocking technique on tsubo

This list is already impressive and we realize that Shiatsu is indeed the heir of Anma. But Shiatsu goes further because it includes other specificities.

The Appaku ho part of Shiatsu should be done with thumbs or fingers on the following points:

- Keiketsu Tsubo: points of the meridians

- Kiketsu Tsubo: out of meridians points

- Aishi Tsubo: natural points unrelated to the meridians (example: the Namikoshi point)

In addition to the technical aspect, it is traditionally requested to study the following aspects to become a practitioner:

- Shindan: diagnosis based on two branches: (So: pathological phenomena and Shin: individual symptoms)

- Anpuku: belly work

- Kyojitsu: study of the conditions of emptiness and excess

- Hosha: toning & sedation methods

- Zofu: study of internal organs

- Teate no michi: care by applying palms.

In this list it would be very useful and interesting to add the study of Kuatsu, the techniques of resuscitation, which gave birth to Western first aid. But this knowledge is almost lost today and it is very difficult to find an expert in the field, while this discipline was still taught by the French Judo Federation in the 60s.

Finally, and finally, students are asked to know the following theoretical bases that we all know because of Chinese thought:

- In Yo Ho (陰陽 法): Theory of Yin & Yang

- Ki (気): the energy that is divided into three branches:

- Ten Ki (天 気): Heaven’s energy

- Chi Ki (地 気): energy of the Earth

- Jin Ki (人 気): human energy

- Gogyo Setsu (五行 說): theory of 5 elements

- Keiraku Chiryo (経 絡 治療): treatment of meridians

The conclusion of all this is obvious: there is indeed a tradition of Shiatsu that is both cultural (in the use of the Japanese body), historical (inheritance of the Anma and works of modern thinkers) and technical ( heritage of Koho Anma). No one is bound to respect these multiple heritages, and it is natural that Shiatsu evolves in many directions. This shows its dynamism and vitality. It’s up to everyone to choose the Shiatsu vision that appeals to them the most. But it is also important to evolve to know one’s roots and stories.

Author : Ivan Bel with kind permission to use the sources of Billy Ristuccia (website: Yotsume Dojo)

Translator : Gilles Datchary

Notes:

- [1] This debate moderated by Mike Mandl, with guests Bill Palmer, Gabriella Poli and Tomas Nelissen, was held on September 20, 2017 in Vienna.

- Book review: “Another self” by Cindy Engel - 30 September 2024

- 24-26 October 2025: Master Class in Vienna (Austria) – Shiatsu and martial arts - 20 August 2024

- Lembrun Summer Intensive Course – July 6 to 12, 2025: Digestive System Disorders, Advanced Organ Anatomy, and Nutrition - 4 August 2024

- Anpuku Workshop with Ivan Bel in London – 7 & 8th, June 2025 - 22 June 2024

- Interview with Wilfried Rappenecker: a european vision for Shiatsu - 15 November 2023

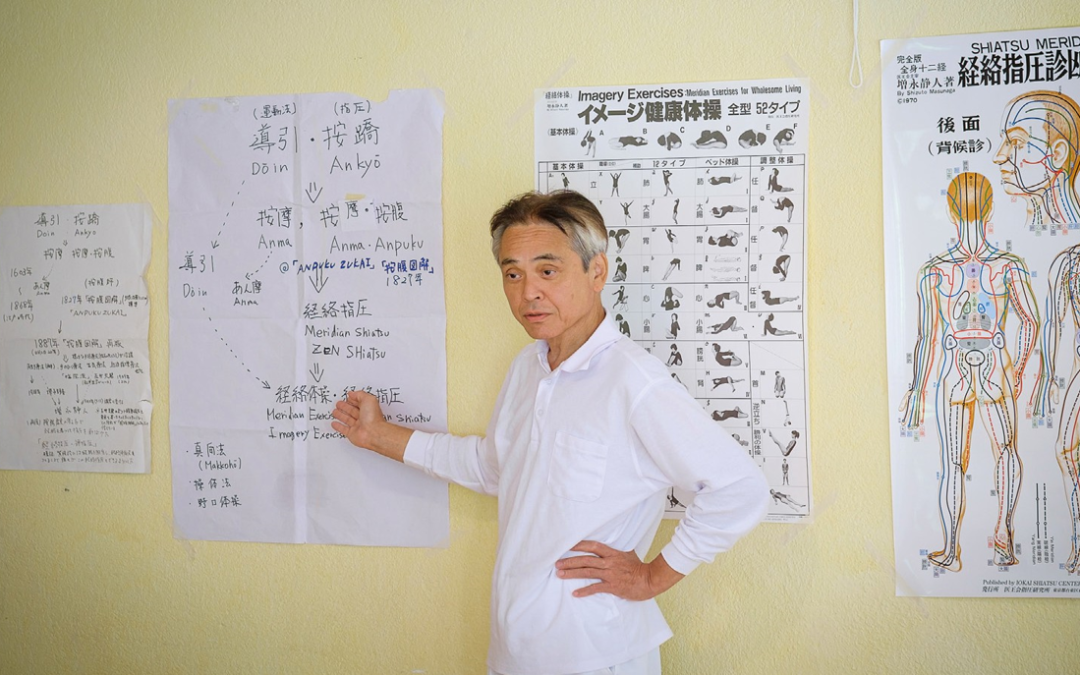

- Interview : Manabu Watanabe, founder of Shyuyou Shiatsu - 30 October 2023