Systems of Hara (abdominal) diagnosis have existed in Oriental medicine since ancient times. Historically speaking, abdominal diagnosis has its roots in Chinese medicine, but as with numerous aspects of ancient Chinese culture, its usage is nowadays extremely limited there. The Japanese, on the other hand, have never dropped the practice of Hara diagnosis[i] and have, over the centuries, elevated it to new heights and to levels of extreme subtlety. In this third part on the work of Shizuto Masunaga, Chris McAlister takes us to the heart of the diagnostic method of the founder of Shiatsu Iokai.

The zones of the Hara

The Hara has a special place in Japanese life and is acknowledged as a center of intelligence, power and vitality in areas of life as disparate as healing, archery and business. It is believed to be the seat of both health and illness and as such is regarded as an optimal place to “read” the energy levels of the patient in a treatment situation.

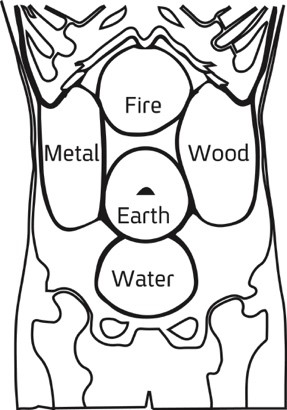

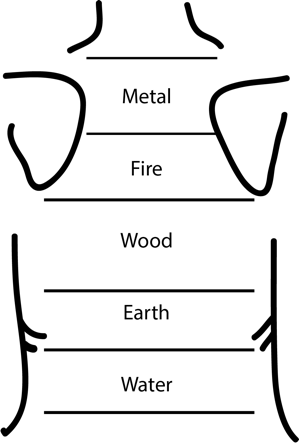

One simple and much-utilised system is framed around the dynamics of the Five Elements:

- Fire (top)

- Wood (left)

- Earth (centre)

- Metal (right)

- Water (bottom)

Simply stated, the practitioner uses both objective and subjective signs in the zones of the hara to assess the relative health of the organs and meridians belonging to the Five Elements. Such signs could for example, include pain, lack of sensation, flaccidity, hardness, nodules, stringy textures, cords, discolouration, whiteness and relative warmth or coolness. The map is still used in many modalities, especially those pertaining to the various Japanese schools of acupuncture, Shiatsu and acupressure.

A rather more detailed map of the abdomen was developed during the late 1600’s in Misono Isai’s Mubun school:

The Mubun method[ii] involves tapping gold and silver needles into the abdomen with a small mallet. It fully disregarded other aspects of Oriental medicine, focusing all attention on the diagnosis and treatment of the abdomen. Today this chart is used solely by practitioners of the Mubun method of acupuncture in Japan. In his landmark text from 2007, In the Footsteps of the Yellow Emperor[iii], Peter Eckman argues persuasively however, that the Mubun school was responsible for the emphasis of Japanese medicine on Hara diagnosis, which was subsequently adopted by many other schools.

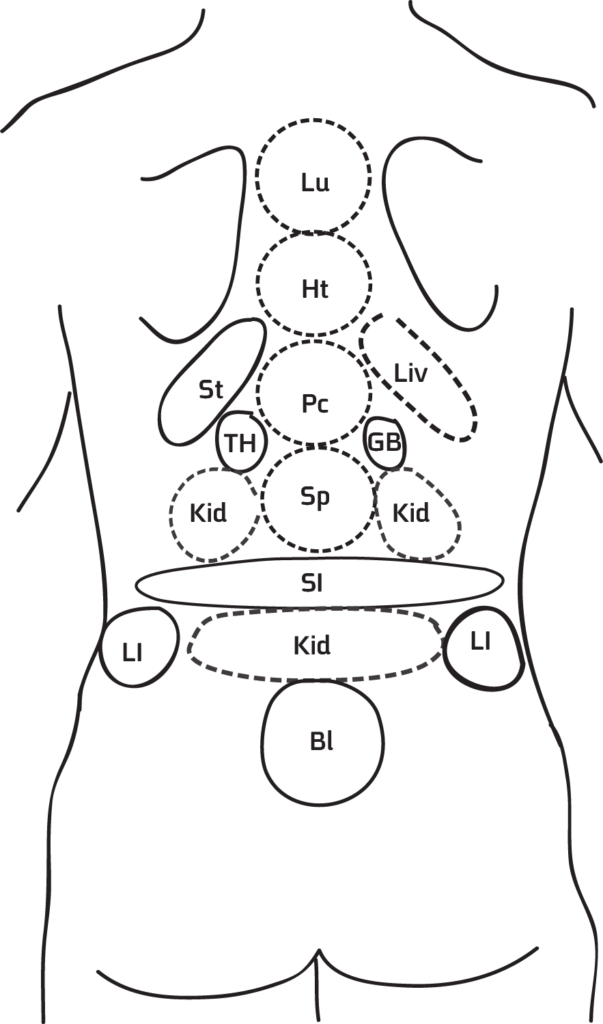

Masunaga, true to his belief in the importance of clinical testing and re-evaluation, designed his own, even more detailed map of the abdominal diagnostic areas:

A casual glance at these three models will show that there are common denominators, but also key differences between them. Let us now take a careful look at them together for the purposes of comparing and contrasting.

To the similarities belong this absolutely central and key phenomenon:

- Fire rises to the top

- Earth settles in the middle

- Water sinks down to the bottom.

This central feature is virtually identical in all three of the above hara diagnosis charts and illustrates a fundamental aspect of traditional Chinese medical philosophy:

- Fire belongs to the heavens and strives constantly upwards.

- Earth revolves on its axis and holds the centre stable.

- Water belongs to the depths and flows inexorably downward.

Masunaga has not deviated from this most ancient of touchstones, and we see clearly how his Heart zone sits atop the hierarchy as befitting the Emperor. Directly below is the Pericardium zone, also commonly associated with Fire. Centrally placed is the Spleen, representing Earth. Occupying the lowest, central area we find the zones for the Kidney and Bladder, the meridians of the Water element.

This is certainly the most striking common denominator, but the similarities do not end there. What we may also observe is that Masunaga continued the work of refining the individual meridian zones which figure prominently in the Mubun system, but which are conspicuously absent from the simpler Five Elements model. One reason for this is very likely the largely unstated and thus implicit attempt by Masunaga to “re-balance” the relationship between the yin and yang meridians of Oriental medicine.

Some background may be useful here: traditionally the yin meridians were also known as Zang. “Zang” in Chinese stands literally for an organ capable of containing something precious. The Heart, Spleen, Kidney, Liver and Lung meridians were regarded as the storehouses for various types of pure and vital energies and substances. (These are respectively Shen, nutritional energy, Jing essence, Blood and Qi). Contrastingly, the yang organs, the Fu, were viewed rather as passageways and run-offs for impure, intermediate and outright waste products.

This in turn has given rise to a tendency in many schools of acupuncture to emphasise the importance in treatment and diagnosis of the yin Zang over the yang Fu. The problem this presents for the bodyworker is quite easy to comprehend: the yin meridians, by their very nature, (i.e. yin) are invariably less accessible, shorter in length and have far fewer points. Compare for example the yang Bladder (67 points) with the yin Kidney (27 points). Another example: the yin Pericardium has 9 points while its yang partner, the Triple Heater, has 23. The Gall Bladder – yang – has 44 points while the Liver, its yin partner in the Wood element, has only 14.

Masunaga made a de facto case for the elevation of the yang meridians both conceptually and – even more importantly – in practice, to the same level as the yin. This represents a kind of levelling or democratization of the meridian network, which is consistently reflected in all aspects of his system: meridian chart, hara zones and back zones. In the absence of any detailed written explanations regarding this “levelling out” effect, we may surmise that both its derivation and impact were primarily clinical.

Another intriguing aspect of Masunaga’s hara zones are the obvious anatomical influences. If we look at the simpler Five Elements chart, we notice that the zone for the Wood element is on the right side as we look at it. Masunaga’s zones for the Liver and Gallbladder are on the left as we look at it – directly underneath the physical location of their respective anatomical organs.

The same anatomical considerations may be said to apply to the Stomach zone and, to a certain extent, the zones for the Small and Large Intestines in Masunaga’s chart. Even his Lung zones, symmetrically matching their Metal element partner, the Large Intestine, are neatly placed at the lower tip of the anatomical lung organs. This provides us with a crystal-clear example of Masunaga’s method of incorporating Western medical knowledge, while also phasing out certain traditional Oriental insights and practices as part of his synthesis.

The sole mystery in Masunagas’s chart of the abdominal zones is the admittedly already rather mysterious Triple Heater (also known as the Triple Warmer, Triple Burner and even Triple Energizer). No clear explanation has been forthcoming as to why the zone for this overarching and omnipresent meridian was placed between the Stomach and Lung zones and above the Bladder zone. In the absence of any explicit recorded statement, we may perhaps infer that this was either: (i) the specific zone located through clinical practice; or (ii) the only space left over…

The Zones of the Back

Numerous classification systems exist for diagnosing via the dorsal area of the human body within Oriental medicine. We can usefully employ the same method of “compare and contrast” to understand the zones of the back as Masunaga envisaged them.

To begin with, we will examine a simple one, again based on the Five Elements model.

Here we see Metal occupying the highest position instead of Fire. This is easily explained by one of the traditional names given to the Lung: “the lid of the organs”, as well as its relationship to the organs of respiration in the upper body: mouth, nose, trachea. The central place is taken by Wood, which we will duly discover is due to the position of the Liver and Gallbladder Shu points (see Shu point chart and glossary), those belonging to the Spleen and Stomach being slightly lower and thus explaining the position of the Earth zone on this chart. Water, master of the depths, assumes its indisputable place as the base and thus the lowest of the zones. No mystery here.

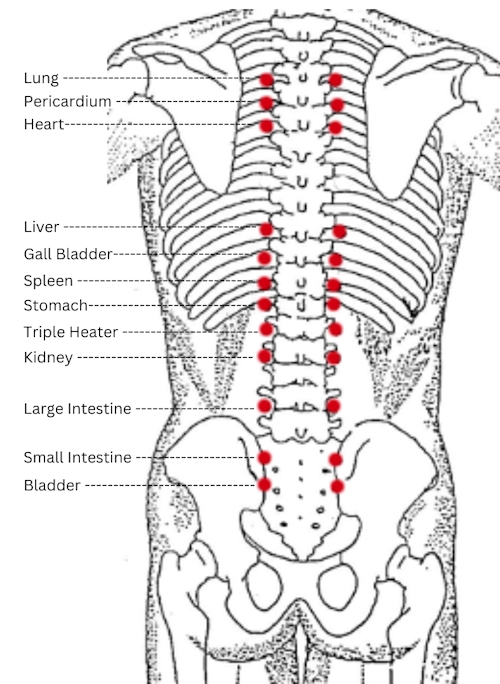

The most common method of mapping and diagnosing from the back is via the Back Shu points. Below and on the left is a map of the Shu points, on which we will find numerous similarities to the Five Elements chart above:

Back Shu points and Masunaga’s back zones

The highest Shu point belongs to the Lung (Metal), followed by those of the Pericardium and the Heart itself (Fire). Skipping discussion of the otherwise fascinating Shu points for Du Mai and diaphragm and passing below the shoulder blades, we find the Liver and Gall Bladder (Wood), slightly above the Spleen and Stomach (Earth). They are in turn followed by Triple Heater and Kidney (Water). Arriving in the lumbar area, we acknowledge but omit discussion of two highly intriguing, but here irrelevant Shu points called Qi Hai (“Sea of Qi”) and Guan Yuan (“Ancestral City Gate”). Instead, we proceed directly to the highly relevant Shu points of the Large Intestine, Small Intestine and finally the Bladder.

Compare this now to the illustration of Masunaga’s back zone chart beside it, where we will once again witness the current of tradition as well as the spirit of innovation in his work. The similarities to the traditional charts are, once again, as interesting as the differences.

In terms of similarities, we find several common threads running through all three systems: Metal or Lung at the top and Water (Bladder in the case of the Shu point and Masunaga zone systems) at the bottom. We will also note a general convergence between the zone for Wood, the Shu points for Liver and Gall Bladder and Masunaga’s Liver and Gall Bladder zones. The same can be said of the zone for Earth, the Shu points for Spleen and Stomach and Masunaga’s Spleen and Stomach zones.

What becomes immediately apparent, of course, is the dissimilarity this now reveals: the element zones are similar to the Shu points – bilateral – whereas Masunaga’s zones are unilateral: Liver and Gall Bladder on the right; Spleen and Stomach to the left. Once again, we notice how this mimics the anatomical location of the Western organs, revealing the influence of Western ideas on Masunaga’s work of synthesis.

The same consideration can be said to apply to the zones for the Small Intestine, here taking the place traditionally allotted to Water and the Kidneys, which are now placed both lower down and to either side. The Large Intestine zones are, much like their hara zones, placed low down and symmetrically to either side, not unlike the Large Intestine Shu points.

Finally, the mysterious Triple Heater is slotted into an intriguing though unexplained location. This time it is squeezed in between the Stomach, Spleen, Pericardium and Kidney zones. Does this in itself reveal something of the nature of the Triple Heater? It is, after all, understood to be “everywhere and nowhere” and “occupying the spaces between everything”.

It should be noted that the zones Masunaga posited on the abdomen and back are not to be regarded as purely diagnostic in function. They are also of use as treatment zones in precisely the same way that the Shu Points are used for both diagnosis and treatment in acupuncture and other styles of traditional Oriental bodywork.

A Simple Diagnostic Paradigm: Kyo and Jitsu

From the myriad of diagnostic methods and modalities available in traditional Chinese medicine, Masunaga chose one. It may be supposed that what he wanted was a tool with the following key qualities: simplicity, practicality and flexibility. The name given to this system is: Kyo and Jitsu.

The words themselves are the Japanese renditions of the terms “xu” and “shi” from Chinese medicine. They are derivations of the more universal yin and yang and have been variously translated. A useful initial observation we might bear in mind is that no Oriental term is capable of one single, direct and definitive translation. Thus, Kyo is commonly rendered as deficiency or depletion, while Jitsu often translates as excess or repletion.

Masunaga described them in the following terms on the back cover of “Zen Shiatsu”:

“If the flow of ki through the meridians is smooth, the person is healthy. If the flow becomes sluggish, the person falls ill. The nature of the flow is analyzed on the basis of the Chinese conception of the duality Yin and Yang into two states called Kyo and Jitsu. In the Kyo state, the flow of ki is sluggish, and the body’s functions dulled. In the Jitsu state, the flow is too rapid, and the body functions are overactive.”

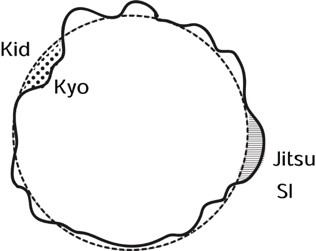

In the main body of the text, he used this now classic diagram to portray the concepts in visual form:

However, we choose to translate the terms, the system is genial in its ease of application. Kyo and Jitsu may be located through touch in the zones of the abdomen, the zones of the back, the meridians themselves or even in the various joints and muscles with regard to left and right sides of the body or even upper and lower body. Additionally, the states of Kyo and Jitsu may be inferred conceptually through signs and symptoms.

What is extremely important to note in Masunaga’s system is the very strong emphasis placed on the Kyo. Depletion or hypo-activity is very often regarded in Zen Shiatsu as the true causative factor in disease. This in turn means that in treatment, attention is often directed away from sites of tension, stiffness, and sharp superficial pain – usually thought to be representative of the Jitsu phenomenon. Attention is instead directed towards areas of weakness, emptiness and deep, dull pain, which are more commonly associated with the Kyo state, and by their very nature somewhat more elusive.

Further, it is deemed advantageous in Zen Shiatsu treatment to begin by treating Kyo. This is in itself a traditional concept, where the reasoning has been that it may be safer to tonify or strengthen an “empty” weakness than to risk aggravating an already overstretched, “full” tension. This idea can be extended to embrace another enormously strategic discovery: if we successfully nourish a weak Kyo area, point or meridian, we may in the very process of doing so find that we have already, to some extent at least, drained away some of the excess from a related, corresponding or nearby Jitsu.

The initial attention paid to the Kyo thus reveals itself to be not only a cautious but also an ergonomic choice, reducing the amount of struggle necessary to calm tension. If the general tendency in Zen Shiatsu thereby veers towards the minimalistic, it also confirms a close kinship with the “bare minimum” ethos of Zen practice and the “bare bones” aesthetics of zen design.

Notes

- [i] To know more about this, read Hara diagnosis: reflections on the sea, Kiiko Matsumot and Stephen Birch, Churchill Livingston edition, 1993

- [ii] To know more about Mubun Daishin go on this paper of academia.edu

- [iii] In the Footsteps of the Yellow Emperor, Peter Eckman, Sinolingua edition, 1998

Author

- Shizuto Masunaga: his way of diagnosing – part.3 - 31 May 2023

- Shizuto Masunaga (part 2): His Creation - 9 January 2023

- Shizuto Masunaga (part.1): a genius on shoulders of giants - 6 October 2022

- The Blackened Pot - 15 June 2022